Why 3 US banks collapsed in 1 week: Economist Michael Hudson explains

Economist Michael Hudson analyzes the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Silvergate, and Signature Bank, explaining the similarities to the 2008 financial crash and the US government bailout.

Economist Michael Hudson analyzes the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Silvergate, and Signature Bank, explaining the similarities to the 2008 financial crash.

In this discussion with Geopolitical Economy Report editor Ben Norton, Hudson also addresses the US government bailout (which it isn't calling a bailout), the role of the Federal Reserve and Treasury, the factor of cryptocurrency, and the danger of derivatives.

Video

Podcast

Transcript

BEN NORTON: Hi everyone, I'm Ben Norton. I have the pleasure of being joined by someone I think is one of the most important economists in the world, Michael Hudson.

And I should say that we should wish Professor Hudson a happy birthday. Today is March 14th. It's his birthday, and he turns eighty-four today. How do you feel Michael?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Just like I feel every other day. I usually feel energetic on my birthday because I'm always working on a new chapter and I tend to write a lot around this period each year.

BEN NORTON: And Michael is extremely prolific. He has so many books. And today we're going to be talking about a lot of topics that he addressed in one of his classic books, which is Killing The Host. And talking about how the financial sector is parasitic for the real economy.

Today we're going to be talking about the banking crisis that we see unfolding in the United States.

This March, three banks have collapsed in the span of one week.

It started at first with a California-based cryptocurrency-focused bank, Silvergate, which collapsed on March 8th, and then two days later Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) went down as well. It went down in the largest-ever bank run.

And that was the second biggest ever to fail in US history. And it was also the largest bank to crash since 2008.

Silicon Valley Bank had $209 billion in assets, compared to the largest-ever bank failure which was Washington Mutual, which had $307 billion in assets, and that was in 2008.

Professor Hudson has been writing about this. He already has two articles that he published. The first is "Why the US banking system is breaking up."

So Michael, let's just start with your basic argument of why you think these banks have been crashing — first Silvergate, then Silicon Valley Bank, and why you think they're crashing, and what the response of the Federal Reserve (Fed) has been.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well in order to understand why they're crashing, you have to compare it to what happened in 2008 and 2009.

This crash is much more serious.

In 2008 and 2009, Washington Mutual collapsed because it was a crooked bank. It was writing fraudulent mortgages, junk loan mortgages. It should have been allowed to go under because of the fraud.

The basic subprime fraud and collapse was widespread fraud throughout the whole financial system. Citibank was one of the worst offenders. Countrywide, Bank of America.

These were individual banks that could have been allowed to go under and the mortgages could have done what President Obama had promised to do.

The mortgages could have been written down to the realistic market values that would have cost about as much to service as paying your monthly rent. And you just would have got the crooks out of the system.

My colleague Bill Black at the University of Missouri at Kansas City described all this in The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One.

So the problem then under the Obama administration — he made an about-face and reversed everything that he had promised his voters.

He had promised to write down the loans, to keep the subprime mortgage people in their houses, but to write down the loans to the fair value and undo the fraud.

What happened instead was, as soon as he took office, he invited the bankers to the White House and said, "I'm the only guy standing between you and the mob with the pitchforks."

[By] "the mob with the pitchforks," he meant mainly Black and Hispanic buyers, mortgagees, who were the main victims of the subprime fraud.

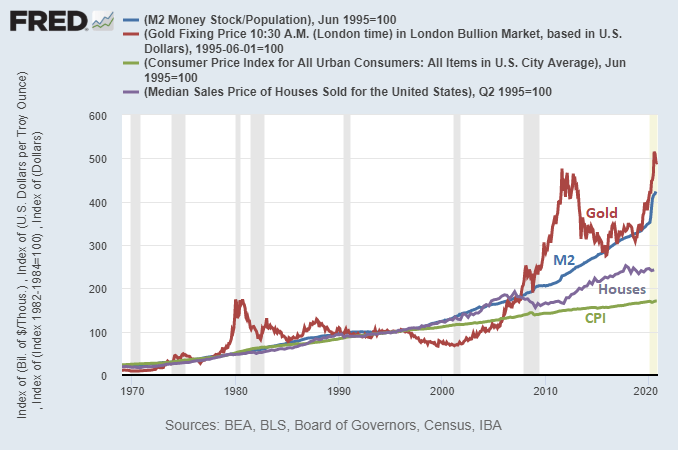

He bailed out the banks and directed the Fed to undertake fifteen years of quantitative easing (QE). And what that was, was the Fed said, "Well the mortgages are worth less than —the value of the property doesn't suffice to cover all of the bank deposits, because the banks have made bad mortgages."

"How do we save the banks that have misrepresented the value of what they have?"

"We're going to slash interest rates to zero. We're going to spur the largest asset-price inflation in history."

"We're going to put nine trillion dollars supporting bank credit — flooding the market with credit — so that instead of real estate prices going back to an affordable level, we can make them even more unaffordable."

"And that will make the banks much richer. It'll make the 1% in the financial sector much richer. It'll make the landlords much richer. We're going to do that."

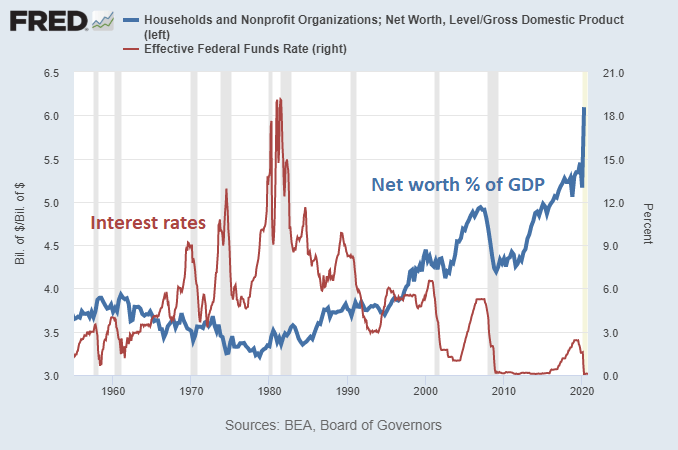

So they spurred — by lowering the interest rates, they created the biggest bond-market boom in American history. From high interest rates in 2008 all the way down to almost zero.

So the result of course was an inflation in stock prices, an inflation of bond prices.

And the result was widening inequality for Americans, because most stocks and bonds are owned by the wealthiest 10%, not by the bottom 90%.

So if you were one of the 10% of the population that owned stocks and bonds, your wealth is going way up.

If you were a part of the 90%, your wages were not going up, and in fact your living standards were being squeezed — not only by the inflation, but by the fact that more and more of your income had to go to paying rent and interest to the FIRE sector — [Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate].

Well finally, a year ago, the Federal Reserve said, "Well there is a problem. Now that COVID is over, wages are beginning to rise."

"We've got to have two million Americans thrown out of work in order to lower wages so that the companies can make larger profits, to pay higher stock prices."

"Because if we don't cause unemployment, if we don't lower the wage levels for America, then profit levels will go down and stock prices will go back down, and our job at the Fed is to increase stock prices, increase bond prices, and increase real estate prices."

So finally they began to raise [interest] rates to — as they put it — "curb inflation."

When they say "inflation," what they mean is "rising wages."

And even though wages have gone up, they have not gone up as much as consumer prices have gone up.

And the consumer prices have gone up, not because of wage pressures, but for two reasons.

One — the sanctions against Russia have sharply increased the price of energy, because Russian oil can't be sold to the West anymore, and Russian agriculture can't be sold to the West anymore.

[Two] — the Democratic party has followed the Republican party in deregulating monopolies. Every monopolized sector of the economy has been raising its prices without its costs going up at all.

And they raise the prices because, they say, "Well, we're raising them because we expect inflation to go up."

Well that's a euphemism for saying, "We're raising them because we can, and we can make more money by raising them."

So the prices have gone up, but the Fed is using this as an excuse to try to create unemployment.

Well, what has happened is that, by solving the problem of wages rising, they've also created a problem that spilled over into the financial sector. Because what they've done is reverse the whole asset-price inflation from 2009 to just last year, [2022].

That's almost a thirteen year steady asset-price inflation.

By raising the interest rates, all of a sudden they've put downward pressure on the bonds. So the bonds that went way up in price when interest rates were falling, now go down in price, because if you have a higher-yielding bond available, the price of your low-yielding bond falls, so that it works out to yield exactly the same.

Also there's been a withdrawal of money from the banks in the last year, for obvious reasons.

The banks are the most monopolized sector of the American economy. Despite the fact that interest rates were going up, despite the fact that banks were making much more money on their loans, they were paying depositors only 0.2 percent.

And, imagine — if you are a fairly well-to-do person, and you have a retirement income, or a pension plan, or if you've just saved a few hundred thousand dollars, you can take your money out of the bank, where you're getting almost no interest at 0.2 percent, and you can buy a two-year treasury note that yields 4 percent or 4.5 percent.

So bank deposits were being drained by people saying, "I'm going to put my money in safe government securities."

Many people also were selling stocks because they thought the stock market was as high as it could go, and they bought government bonds.

Well what happened then is that all of a sudden, the banks — especially Silicon Valley Bank — found themselves in a squeeze.

And here's what happened.

Silicon Valley Bank and banks throughout the country were flooded by deposits ever since the 2020 COVID crisis.

And that's because people were not borrowing to invest very much. Corporations were not borrowing.

What they were doing was building up their cash.

[SVB's] deposits were growing very very rapidly, and it was only paying 0.2 percent on the deposits — how is it going to make a profit?

Well it tried to squeeze out every little bit of profit that it could by buying long-term government bonds.

The longer term the bond is, the higher the interest rate is.

And even the long-term government bonds were only yielding let's say 1.5 percent, maybe 1.75 percent.

They took the deposits that they were paying 0.2 percent on and lent them out at 1.5, 1.75 percent.

And they were getting — it's called arbitrage — the difference between what they had to pay for their deposits and what they were able to make by investing them.

Well here's the problem. As the Federal Reserve raised interest rates, that meant the value of these long-term bonds — the market price — steadily fell.

Well most people who saw this coming — every CEO that I know sold out of stocks, sold out of long-term government bonds.

When the Federal Reserve head said that he was going to raise interest rates, that means you don't want to hold a long-term bond.

You want to keep your money as close to cash as possible. You want to keep it in three-month Treasury bills. That's very liquid. Because short term treasury bills, money market funds — you don't lose any capital value in that at all.

But the Silicon Valley Bank thought — well they were still after every little bit of extra they can get, and they held onto their long-term bonds that were plunging in price.

Well, what you had was a miniature of what was happening for the entire American banking system.

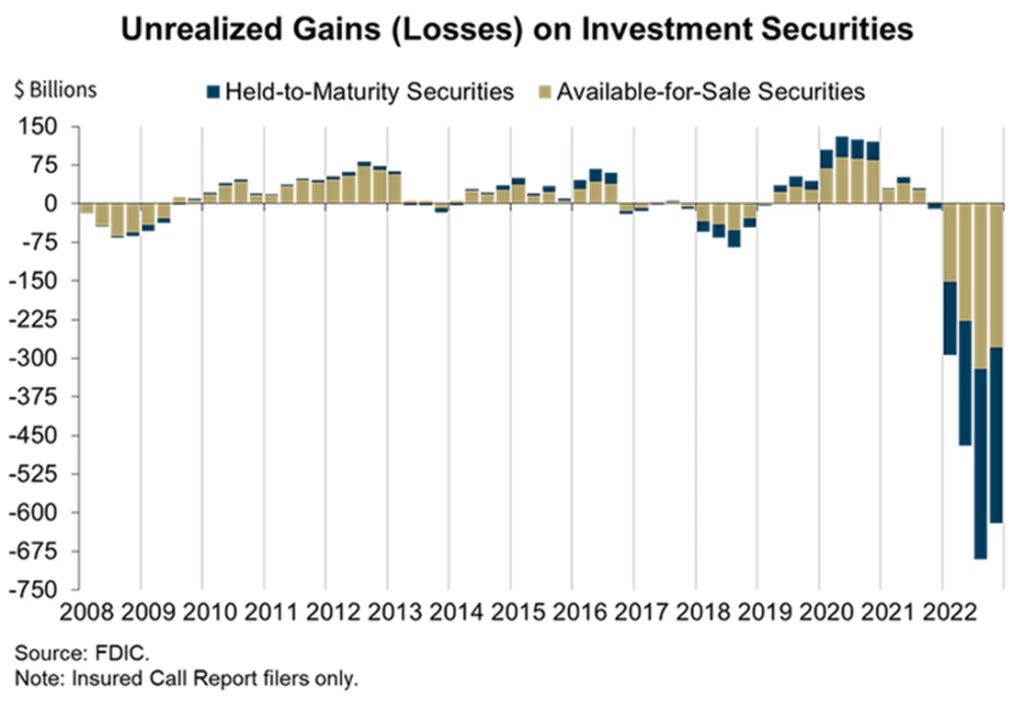

I have a chart on that, on the market value of the securities that banks hold:

Now, when Banks report to the Federal Reserve, that's exactly it. When they report — this shows the actual market value.

If banks valued their assets just what they were worth on the market, they would have plunged just like you see at the bottom there.

But banks don't have to do that. Banks are allowed to represent their assets according to the book value that they paid for them.

So Silicon Valley Bank, and other banks throughout the system, have been carrying all their long-term mortgage loans, packaged mortgaged, government bonds, at the price they paid for them — not the declining market price.

They figured — "Well, we can ride this out and hold it to maturity in twenty-five years as long as nobody in the next twenty-five years actually withdraws their money from the bank."

It's only when bank customers and depositors pull their money out that they decide that, "Wait a minute. Now in order to raise the cash to pay the depositors for the money they're taking out, we have to sell these bonds and mortgages that we've bought. And we have to sell them at a loss."

And so the bank began to sell the bonds and the packaged mortgages at a huge loss. And they were losing capital.

Well as it happens, Silicon Valley Bank isn't a normal bank. A normal bank you think of as having mom and pop depositors, individuals, wage earners.

But almost all the deposits — I think over eighty percent of the deposits at Silicon Valley Bank — were by companies. Mainly high-tech companies that were sponsored by private capital — special purpose private capital acquisitions.

And they began to talk amongst each other, and some of them decided, "Well it looks to me like the bank's being squeezed. Let's pull our deposits out of the small bank and put them in a big bank like Chase Manhattan or Citibank or any of the big banks that the government says are too big to fail."

So you know that their money will be safe there. So there was a run on deposits.

So the the problem that Silicon Valley Bank and other banks have is not that they'd made bad loans. It's not that they had committed any fraud. It's not that the US government couldn't pay the bills. It's not that the mortgagers couldn't pay the bills.

It was that the market price of these good loans to solvent entities had gone down and left the bank illiquid.

Well, that is what is squeezing the entire financial sector right now.

So just as the quantitative easing was flooding the economy with enough credit to inflate asset prices for real estate, stocks and bonds — the tightening of credit lowered the asset prices for bonds certainly, for real estate too.

For some reason the stock market has not followed through. And people say, "Well, there is an informal government Plunge Protection Team (PPT) that's artificially keeping the stock market high, but how long can it really be kept high?"

Nobody really knows.

So the problem is that the 2009 crisis wasn't a systemic crisis, but now, the rising interest rates have created a systemic crisis because the Federal Reserve, by saving the banks' balance sheets by inflating the prices for capital assets, by saving the wealthiest 10% of the economy from losing any of their money — by solving that problem they've boxed themselves into a corner.

They cannot let interest rates rise without making the entire economy look like Silicon Valley Bank. Because that's the problem. The assets the banks hold are stuck.

Now a number of people have said, "Well why didn't the banks — if they couldn't cover their deposits — why didn't they do what banks did in 2009?"

And in 2009 the banks — Citibank, Chase Manhattan, all the big banks — went to the Federal Reserve and they did repo deals.

They would pledge their securities and the Fed would lend them money against their securities.

This wasn't a creation of money.

None of this quantitative easing appeared as an increase in the money supply. It was all done by balance sheet manipulation. The banks were able to go to the Fed.

Or instead of selling the bonds, people said, "Why couldn't Silicon Valley Bank simply borrow short-term money? You want to pay out the depositors? Okay, borrow the money, pay the four percent, but don't sell — you know, it's not going to last very long. Once the Fed sees how systemic the problem is, they'll certainly turn out to be cowards and roll back the interest rates to what they were."

But there's a problem. If the the repo market — in other words, the "repo market" is the "repossession market" — it's the market that banks go to if they want to borrow from larger banks. You want to borrow overnight credit. You want to borrow from the Federal Reserve.

But if you borrow in the repo market, the bankruptcy law was changed in order to protect these sort of non-bank lenders, and it was changed so that if a bank makes a currency swap — if it says, "I'm going to give you a billion dollars worth of packaged the government bonds and you'll give me a loan" — if the bank then goes under and becomes insolvent, as Silicon Valley did, the bonds that it pledged for repo are not available to be grabbed by the bank itself to make the depositors whole.

The repo banks — the large banks — are made whole.

Because Congress said, "We have a choice. Either we can make the economy rich or we can make the banking sector rich. Who gives us our campaign contributors? The banks."

"To hell with the economy. We're going to make sure the banks don't lose the money, and that the 1% that own the banks don't lose money. We'd rather the voters lose the money because that's how democracy works in America."

So the result is that the — there was a lot of pressure against SVB trying to protect itself in the way that banks were able to do back in 2009. All they did was sell the existing securities they had in order to pay the depositors before they were closed down on Friday afternoon — before closing hours — and that led them to the problem today, before President Biden decided to bail them out and then blatantly lied to the public by claiming it's not a bailout.

How can it not be a bailout? He bailed out every single uninsured depositor because they were his constituency. Silicon Valley is a Democratic Party stronghold, as most of California is.

There's no way that Biden and the Democratic Party was going to let any wealthy person in Silicon Valley lose a penny of their deposits, because it knows that it's going to get huge campaign contributions in gratitude for the 2024 election.

So the result is that of course they bailed out the banks and President Biden weaseled his way out of things by saying, "Well, we didn't bail out the bank stockholders. We only build out the billions of dollars of depositors."

BEN NORTON: It's very revealing to see how the financial press treated Silicon Valley Bank.

In fact, just before — on the eve of it imploding — Forbes described SVB as one of "America's Best Banks" in 2023. And that was for 5 years straight, praising this bank.

And I think it's important to go look at SVB's website and to see how it portrayed itself, what it was boasting of.

If you go to the Silicon Valley Bank website, they boast that 88% of "Forbes' 2020 Next Billion-Dollar Startups'' are SVB clients. "Around 50% of all US venture capital-backed tech and life science companies bank with SVB."

And in fact, just before it imploded, 56% of the loans that SVB had made were to venture capital firms and private equity firms.

And if you go down on their website, they boast "up to 4.5% annual percentage yield on deposits," which is incredible. I mean most banks offer 0.2% yield.

SVB wrote on their website, "Help make your money last longer with our startup money market account. Like with the savings account you'll earn up to 4.5% annual percentage yield on deposits."

MICHAEL HUDSON: "Up to." I could say, why don't they say "Up to 50% a year." — anything you want.

I think in this case they were factoring capital gains into it — that means asset-price gains — this wasn't an income yield so much. It was an overall yield, making the depositors part of the mutual speculation.

But the depositors — we know that eighty percent were people like Peter Thiel. They were large private-capital firms.

And one of the problems is, if you have a lot of well-connected rich people who are the major depositors that they're talking to in this case, they talk to each other.

And when they see that there's no way that the bank can pay anywhere near 4.5% anymore, they jump ship.

And that's exactly what happened. They talked to each other and there was a run on the bank.

Now, most people think of a run on the bank as being "the madness of crowds."

This wasn't the madness of crowds. The crowd was not mad. The bank may have been mad, but the crowd was perfectly rational.

They said, "Look, I think the free lunch is over. Let's pull our money out. What we want now is not to hope and pray for a 4.5% return — let's just move for safety."

If you have a billion dollars, you're more concerned with keeping that billion dollars safe than actually making an income on it. And I think that's what happened.

And when you say "up to" — yeah, that's funny language.

BEN NORTON: And Michael, I know you're friends with Pam Martens and Russ Martens over at WallStreetOnParade.com that always do great reporting.

MICHAEL HUDSON: They've done a wonderful job of following all of this. They say, if there's anyone who shouldn't be bailed out, it's the wealthy billionaire depositors of that bank.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, they described Silicon Valley Bank as a "Wall Street IPO pipeline in drag as a federally insured bank."

And I just want to read what they wrote here which really summarizes it very well: "SVB was a financial institution deployed to facilitate the goals of powerful venture capital and private equity operators by financing tech and pharmaceutical startups until they could raise millions or billions of dollars in a Wall Street Initial Public Offering (IPO)."

You mentioned, Michael, that the US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen claimed that the US government is not going to bail out the depositors — these private equity firms and such and startups at SVB — but in reality only $250,000 of their deposits were actually federally insured, but we were seeing that actually the US government is ensuring that all of their deposits, including above $250,000, is going to be paid to them.

So essentially, what the Federal Reserve — backed by the Treasury with the $25 billion war chest in supporting this operation — what they're essentially saying is that deposit insurance on commercial banks in the United States, including ones with very high interest interest-bearing deposits — it's basically infinity.

There is no limit on federally insured accounts. It's no longer actually $250,000 — which only incentivizes other firms in the future to deposit their earnings into very risky banks that offer very high interest rates they can't pay out, because they know that the US government will bail them out.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well Janet Yellen also said that Ukraine was going to win the war with Russia. Sort of the reincarnation of Pinocchio.

You're never going to have a Federal Reserve head say that there's going to be a problem.

Bankers are not allowed to tell the truth.

That's why — one of the worst things that can happen to a banker is if they get COVID. Because when you get COVID sometimes, you're not able to lie quickly, and it's a surefire way of losing the job.

That's part of it. But there's another reason.

If you have a banker be aware of the systemic risk that I just explained — the risk that is for the whole economy if it ever tries to go back to normal, which it can't again without causing a crisis — then you're disqualified for the job. Or you're called overqualified.

In order to be a bank examiner or a bank regulator, you have to believe that every problem can be kicked down the road. That there are automatic stabilizers and the market is going to solve everything thanks to the magic of the marketplace.

And if you don't believe that, you're a blackballed and are never going to be promoted.

So the last person you're ever going to want to explain anything, whether it's Alan Greenspan or his successors, is the head of the Federal Reserve.

BEN NORTON: Michael, I want to talk about the scheme that the Federal Reserve has created in order to bail out Silicon Valley Bank and its clients without calling it a bailout.

I'm going to look at a very good Twitter thread that was done by the post-Keynesian economist Daniela Gabor.

She's tweeted that she has spent fifteen years researching central banks collateral, and she has never heard a single central banker contest the common wisdom that there should be "haircuts."

Instead, what we see is the Fed is paying par value.

So the Fed has this program called the Bank Term Funding Program, and essentially it's giving extremely favorable loans to Silicon Valley Bank and other banks, which are essentially government subsidies.

And instead of using as collateral the Treasury securities and other assets that are owned by Silicon Valley Bank — or at least that were — instead of using their market value, the Federal Reserve is using the value at par — the face value that was printed on the Treasury securities that are held by SVB and other banks that need to be bailed out.

So essentially what they're saying is that, only average working people are subject to the discipline of the market.

But banks — they don't actually have to go along with market value for their securities.

They can be bailed out by using as collateral the values of what they originally bought the security at before the Fed raised interest rates and the price of those bonds decreased.

So in short what it is, is socialism for the rich for big corporations and for the commercial banks, and capitalism for everyone else.

Daniela Gabor said she's never seen this in fifteen years of research. Have you ever seen something like this?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well this is what I said at the very beginning of our discussion today.

I said, the banks are able to carry their assets at the price they purchased them. That was called the "book value" — not the "current market value."

For years, in the 1960s and 1970s, if you had banks or a corporation carrying real estate at book value, people were looking over these balance sheets saying, "Aha, they're going to value their real estate at what they bought it for in the 1950s and now it's tripled in value. Let's raid that corporation and take it over, break it up, and sell the real estate."

That was how money was made in the 1960s and 1970s and even more in the 1980s.

But that's when asset prices are going up.

But when you mark to "purchase price" — "book value" — instead of the "market value," you're going to have this disparity. That's exactly the problem.

And you're quite right about the double standard that the government has.

Look at the double standard with the student loan debtors. They are unable to pay their student loans without making a big sacrifice. But Biden has made sure that they're not going to be bailed out because he's the man who sponsored the bankruptcy bill saying that student loans are not subject to bankruptcy laws to be written down.

Every other kind of asset, if you go bankrupt, can be written down to the current market failure for what you owe. But not student loans.

They are kept sacrosanct.

There's a diametric opposite economic philosophy when it comes to what wage earners and consumers owe, and what the financial and real estate sector owes.

The Biden Administration and the Republicans say that no billionaire should lose a single penny. No bank or real estate company should owe anything. We will guarantee that bailout — they are risk-free.

We've transferred all of the risk onto the voters who put us in power, because we say that, "Maybe you'll be a billionaire someday. You don't want to hurt them, do you?" or whatever their politicking is.

So this double standard is what is squeezing the economy now. By not permitting the financial sector from taking a penny loss, somebody has to lose. And the losers are the non-financial economy — the real economy of production and consumption.

BEN NORTON: Michael, another factor in this is crypto. While all of this is happening, it's also in the wake of a disastrous collapse in big parts of the cryptocurrency industry.

You yourself have always been very skeptical and have criticized this crypto industry and you can talk about that — I mean I've done many interviews with you over the years. Going back on the record people can see that you were proven right about this.

Of course Silicon Valley Bank as its name suggests is definitely involved in the tech sector and Silicon Valley.

But before SVB collapsed we saw Silvergate collapse, and Silvergate was very heavily invested — or at least many of its depositors were companies invested in crypto.

And then on March 12th there was another bank that went down which — unlike SVB and Silvergate, which were in California — the third bank to go down was Signature Bank which is based in New York City. And thirty percent — almost one-third of Signature Bank's deposits were cryptocurrency businesses.

So maybe you can talk about crypto's role in all of this. And of course this comes at a time when Sam Bankman-Fried — the fraudster who ran the FDX exchange — he was exposed to the world for committing literal fraud, and losing billions of dollars really overnight.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well the whole mythology and fantasy of crypto has been burst, especially with Bankman-Fried.

Crypto was supposed to be — they called it peer-to-peer lending. The peer-to-peer lending was, the person who bought the crypto took money out of the bank and paid for crypto with a bank transfer fee — was one peer.

Who's the other peer? The other peer was Bankman-Fried, and he could do whatever he wanted with his money.

The crypto cover story was, "Well, we know that the economy's messed up and we don't like big government and we don't like the bank, so here's an alternative to the banks, putting your money in that bank and putting your money, depending on government fiat currencies."

So people would put their money into crypto, thinking, this is something different from the banks. And yet it turns out — what did the crypto companies do?

If you get a billion dollars of inflow by people who want an alternative, what are you going to do with a billion dollars?

Well Bankman-Fried simply bought luxury real estate and gave money to the Democratic Part and a few Republicans for campaign contributions to buy influence.

But most of the crypto was put in Silvergate Bank or other banks, or government securities. I mean, where else are you going to put a billion dollars inflow?

You get a bank transfer from a bank. It goes into your bank account — you have to have a bank account somewhere to hold it. And what do you do?

The money that goes into crypto ends up in the very banks or the government securities that crypto's supposed to be an escape from.

So all that crypto is, is a disguised bank or a mutual fund that has its money in banks and government securities.

Except it has secrecy, so that if you're a criminal or a tax evader or a crook and you don't want the government to know what you have, you're willing to give a premium.

Just like the cocaine cartel who will pay ten percent or twenty percent for money laundering.

Crypto was a vast money laundering operation wrapped in an idealization — a fantasy — that it was an alternative to banks and government money, when of course the backing for the crypto was banks and government money.

Obviously when people begin to realize this, and saying, "Wait a minute, who is running the cryptocurrency that we're holding? We don't know what it is." Because it's crypto — that's why it's called crypto. And it can't be regulated, because the government can't know what's in it or who's paying what, because it's crypto.

So there's no way of regulating crypto, and needless to say, every mafiosi — every sort of financial crook — finds it's like taking a candy from a baby. All you have to do is say that we have a an idealistic libertarian answer to socialism.

So crypto was the libertarian answer to socialism. And we've seen — I think socialism won that particular fight.

The banks of course — when people were selling the crypto, the cryptocurrency had to draw on its bank account. And when it drew on its bank account, the banks were left without money.

The banks that had to pay the crypto company to pay the crypto seller had to sell their bonds and packaged mortgages and take a capital loss on assets that they were carrying at original book value or purchase price, but that they were only getting the market price for.

So, the whole unraveling of all of this — reality raised its ugly head.

BEN NORTON: Professor Hudson you've written in an article about this, which is "Why the US banking system is breaking up." And then you followed up and you said that "the US bank crisis is not over." And you warned that it could spread.

And I just want to go over this briefly again just these numbers here.

The biggest bank to ever fail in US history was Washington Mutual and I was in 2008 during the financial crash and it had $307 billion in assets.

The second biggest bank ever to collapse in US history was Silicon Valley Bank with $209 billion in assets. So pretty close to Washington Mutual.

And Signature Bank was the third biggest bank to collapse, which had $118 billion in assets.

So clearly there are parallels to the 2008 crash.

But in your article you also pointed out that there are parallels to the Savings and Loan (S&L) Crisis of the 1980s. So what can we learn from the 1980s S&L crash and also the 2008 crash?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well I want to first of all challenge what you said about Washington Mutual being the biggest bank to go under.

This is not at all the right way to look at it.

What is important to look at is, what banks were insolvent.

Sheila Bair wrote in her autobiography that there was one bank that was worse than all the others. It was totally insolvent — not only incompetently managed but crooked. That bank was Citibank.

But Citibank was looked over by Obama's Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner — who had worked with Bob Rubin, who was the protector of Citibank — so the fact is that not only Citibank — Citigroup— but all the big banks — Sheila Bair, who was head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, said, the banks are insolvent.

She was pressing. She said, "Look, Citibank should go under. Let's clean it up. Let's take it under and clean out the crooks."

And Geithner said, "No, the crooks are us. That's our game."

So the key to look at isn't what banks actually were permitted to go under — the really crooked banks like Washington Mutual — but what banks are insolvent. Citibank and Wells Fargo, she mentioned. These were the banks that had the junk mortgages. Bank of America. The banks were insolvent.

And when I say that the problem is just beginning, it's just beginning because the problem that the financial sector and the banking sector has today is endemic to finance capitalism.

The charts that I've made in Killing The Host and also in The Destiny of Civilization — the financial sector grows by interest-bearing debt, and that's an exponential system. Any interest rate has a doubling time. Any interest rate goes exponentially.

But the economy doesn't keep track. It goes on an S-curve, and it goes slower and slower, and then it turns down. That's the business cycle. And it's depicted as a kind of sine curve, up and down.

The problem is that the economy can't keep pace with the ability with the debts that it owes — the ability to pay the exponentially rising debt does not keep pace with this growth of debt.

That makes a collapse inevitable.

This disparity between the growth curves of debt and the growth curve of the economy has been known for 5,000 years. It was already documented in Babylonia in 1800 BC.

We have the textbooks — the mathematical textbooks — that scribes were trained in. Antiquity knew this. Aristotle talked about it.

Everybody knows about this, but it's not taught as part of the financial curriculum.

The financial sector grows by different mathematical laws then the economy grows in. And that's what makes it inevitable.

The Savings and Loan Crisis was somewhat different. It is worth mentioning, because much of it was the result of a fraud — again as Bill Black has explained.

But here is the problem in the Savings and Loans and savings banks. I discussed this in the article that you just cited.

The savings banks and S&Ls lent mortgage money, and they would — basically, when I was working in the 1960s, interest rates were going up from about 3.5 percent to 4.5 percent for mortgages.

And the banks would take deposits and they'd pay maybe a 2.5 percent interest and they'd make loans at maybe 3.5 percent for a thirty-year mortgage.

So of all of this sort of happened normally until the late 1970s. And in the late 1970s — because of the Vietnam War — the interest rates steadily rose because the US balance of payments was getting squeezed.

And finally you had inflation because of the war-induced shortages — "Pentagon capitalism" — and so Paul Volcker raised the interest rates to 20 percent.

Well imagine what happened? Even though they came down from 20 percent, after 1980, they were still very high.

Well here's the situation — the SNL's were in much the same situation that bank depositors were in the last few years.

You could get a very low rate of interest from the banks or a high rate of interest by putting your money in government securities or corporate bonds or even hunk bonds that were paying a lot of money.

So people took the money out of the banks and a bought higher yielding financial securities.

Well the banks were squeezed, because the banks could not pay. When interest rates went up to 6 percent, 7 percent for mortgages — banks couldn't simply charge their mortgage customers more because the mortgage customer had a thirty-year loan at a fixed rate of interest.

So there was no way the banks could earn enough money to pay the high interest rates that were in the rest of the economy. And as a result they were pushed under, and the commercial banks had a field day.

Sheila bear told me that the banks raped the — she didn't that used that word — the savings banks.

She said, "They said they were going to provide more money for savings bank depositors, and what they did was empty it all out and just pay themselves higher salaries."

So there are I think no more savings banks, hardly — no more S&Ls. They were all cannibalized by the large Wall Street Banks emptied out as a result and that transformed the financial structure and the banking structure of the American economy.

Well that transformation, and that squeeze, of getting rid of a whole class of banks is now threatening the smaller banks in the United States, the smaller commercial banks.

Because they're in the situation of being sort of left behind. In the sense that, if only the largest banks are too big to fail — in other words, they're such big campaign contributors and they have so many of their ex officials running the Treasury or serving as Treasury officials or going into Congress or buying Congressman — that they're safe.

And people who have their money in smaller banks — like a Silicon Valley Bank and the others you've mentioned — are nowhere near as safe as the Too Big to Fail banks.

And if a bank's not too big to fail, then it's small enough to fail, and you really don't want to keep more than $250,000 there because that's not insured, and you don't know how long Biden can get away without bailing out the wealthy depositors and just sticking it to the rest of the economy.

At some point, he just can't be a crook anymore.

BEN NORTON: Michael you've emphasized that, after the 2008 crash, in addition to bailing out the big banks and all this and the idea of Too Big to Fail — one of the ways that the US had a so-called recovery — although you pointed out it wasn't really a recovery — is through quantitative easing.

And you can see quantitative easing really is a kind of drug for the economy, where money was so cheap, interest rates were so low — I mean, now that interest rates are rising — the federal funds rate is going up — it makes it more expensive to get money and this bubble that was created by the Fed is is beginning to burst.

And you've argued that this is maybe going to push them back toward quantitative easing, although Jerome Powell has insisted that he's potentially going to continue increasing the federal funds rate.

MICHAEL HUDSON: That was on Friday [March 10] he said that. Yesterday he withdrew. He said, "I'm sorry, I'm sorry. We crashed the banks. Never mind. Never mind. Now that I realized that I'm not only hurting labor, but I'm hurting our constituency, the 1%, of course we're going to roll it back. We're not going to — don't worry 1%, give your money to the party. We're going to make everything okay for you."

BEN NORTON: If you look at a graph of asset price inflation, we see that it seems like the economy in the US is at a point where it's so financialized, and it relies so much on these bubbles, that it doesn't seem like it can survive without low interest rates and without quantitative easing.

So you've argued that this crisis is here to stay. There needs to be fundamental systemic change.

It's going to either be stagflation, with the continuation of these policies of QE and low interest rates, or it's going to be economic crisis like we're seeing now.

MICHAEL HUDSON: This is the corner into which the Fed has painted itself.

We're in the culminating part of the "Obama depression." This is what Obama set in motion by bailing out the banks and supporting the banks instead of the economy as a whole.

Obama and Geithner and Obama's cabinet declared war on the economy by the 1%.

And the amazing thing is that the economy doesn't see how dangerous what he did was, and how consciously he sold out the voters that have put trust in them — to do everything he could to hurt them, because the degree to which he could hurt the economy was the degree to which the 1% or the 10% was able to make a killing.

So this is not the class interest that Marx talked about. It's not the class interest of employers versus wage earners.

It's the finance class allied with the real estate and insurance class — the FIRE section — against the economy at large — the real economy of production and consumption.

That is what we're seeing, and something has to give.

And in every case both the Republicans and the Democrats say, "If something has to give, we're willing to shrink the economy in order to protect the the financial, insurance, and real estate sector from taking a loss, because that's where the 10% have it's assets."

We're not in industrial capitalism anymore —we're in finance capitalism. And the way that finance capitalism works is very different from the dynamics of industrial capitalism as was forecast in the nineteenth century.

BEN NORTON: Michael, as we start to wrap up here I want to ask you about corruption. This is something that you mentioned in your articles analyzing the SVB crash and other banks crashing.

You talk about campaign financing, which you address, but also regulatory capture is I think an important point.

And you wrote that, "To understand this, we should look at who the bank regulators and examiners are. They are vetted by the banks themselves, chosen for their denial that there is any inherent structural problem in our financial system. They are True Believers that financial markets are self-correcting by automatic stabilizers."

Talk about the concept of regulatory capture and how really it's just corruption, but we don't call it that. Because the US acts as if other countries are corrupt but the US isn't corrupt.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well the center of this corruption — again my colleague Bill Black has explained this — if you notice, who were the bank regulators over the Silicon Valley Bank and the others?

These banks that have gone under are all regulated by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. If there's any bank board that is totally run by the banks that it regulates, it's the Federal Home Loan Bank Board.

And they look at themselves as "protecting" the banks under their authority. Instead of regulating them, they say, "How can we help you make more money?"

Before that the most corrupt regulator was the [Office of the] Comptroller of the Currency group.

Now, banks have a choice. The banks are able to choose what regulator is going to regulate them.

If you're a banker and you want to be a crook, you know just who to go to.

"I want to be regulated by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board because I know that they'll always let me do anything I want."

"They owe their job to the fact that I can get them fired at any time if they do something that will not let me do whatever I want."

"If they try to say that what I'm doing is fraudulent, I'll say, 'This is socialism! You're regulating the market! This is market regulation, come on! Theft is part of the market, don't you get that?' "

And the regulator later said, "Oh yes, you're right — the free market under the libertarian Federal Home Loan Bank Board — fraud is part of the free market. Theft is part of the free market. Anything else is socialism, so of course we're not socialists.."

Of course you can do whatever you want and as long as you have bank regulators like that who believe that, as Alan Greenspan put it, "Why would a banker ever cheat somebody? If he cheated somebody he wouldn't have them as customers anymore."

Well, if you ever have been pickpocketed in Times Square anywhere else in New York, you notice that the pickpocket doesn't say, "Gee, I better not steal the wallet of this guy because then he'll never trust me again."

You're never going to meet the guy again — it's a hit and run. And that's how the financial sector has worked for the last century, and already for the early twentieth century.

There were critics of how banks were structured, and the British critics especially. During World War I the argument came out, "Maybe Germany is going to win the war because they have a much more industrially-organized banking system." Banks had been industrialized.

But the British banks — and stockbrokers especially — are hit-and-run and just want a quick payout and leave the company emptied out.

Well the way to make money most quickly, if you're a financier in America, is asset stripping — you borrow money, you buy out a corporation, you load it down with debt, and empty it out, and leave it as a bankrupt shell.

That's finance capitalism. That is what you're taught to do in business schools. That's how the market economy works.

Raid a company, take it over, sell off the wealthy assets, pay yourself a management fee, pay yourself a huge dividend — this is why I think Bed Bath & Beyond is going under. It's why a whole bunch of companies are going under.

You borrow money, you take over a company, you let the company borrow money, you pay it to yourself as the new owner as a special dividend, and then you leave the company owing a debt with no current income able to cover the debt, and it goes bankrupt. And you say, "Whelp, that's the market."

And of course it doesn't have to be the market. It doesn't have to be this way, but that's the way in which the market is structured.

And you'd think that this is the kind of thing that academic economics courses would teach about. But instead of teaching people how to make an alternative to this, and how to avoid this kind of a ripoff economy and smash and grab economy, they show you how to do it.

So, given the way in which public consciousness is taught and the skill of financial lobbyists and telling people that they're getting rich to borrow more money to buy a house whose price is going to go up and up if only they take on more and more debt.

If people imagine that the economy's recovering by taking on debt to make housing more expensive and stocks and bonds and hence retirement income more expensive, then you're living in an inside-out world that turns out to be a nightmare.

BEN NORTON: Well to conclude here, Michael my last question is: Where you think we should be keeping an eye on the US economy? What other financial institutions could be next?

You wrote in your analysis that the Biden administration is simply kicking the can down the road until the 2024 election. That these are fundamental systemic problems and there may very well be more banks that crash in the next weeks, months, years.

So, where should we be looking, and what's the final word you want to leave us with?

MICHAEL HUDSON: The word is: "derivatives."

There are $80 trillion of derivatives — that is, bets — casino bets — on whether interest rates will go up or down — whether bond prices will go up or down.

And there's been a gigantic increase in the volume of bets that banks have made — maybe a hundred times as large as it was back in 2008-2009.

And one of the reasons it could grow so much is, with interest rates of almost zero, people could borrow from the bank and essentially go to the races and make bets on currencies, exchange rates, interest rates.

But now that interest rates are beginning to go up, it costs more to make the bets, and even if you bet right on a derivative — you can put down a penny and buy a $100 bond and bet that this bond is going to go up one penny.

And if it goes up one penny, you've doubled your money. But if it goes down one penny then you've lost it all.

This is what happens when you have a highly leveraged bet on derivatives or something else.

The derivatives are what everybody's worried about, because there's no real accounting for them. We just know that — I think JP Morgan Chase has maybe [$55 trillion] in derivatives.

Ellen Brown has just written a wonderful article on derivatives that's all over the internet, and she's a lawyer as well as a bank reformer.

The next big crash is going to be some bank that's made a wrong bet in derivatives and the wrong bet has just wiped out all the bank capital. What is going to happen then? That's the —as they say, the next shoe that is going to fall.

BEN NORTON: Well Michael, I want to thank you so much for joining us to explain these important topics.

Not only I'm just for joining us, but for joining us specifically on your birthday. Happy birthday, it's a real pleasure. Thank you so much for spending your time with us.

I want to invite everyone to go check out Michael's website at michael-hudson.com.

There you can find links to his articles, to his books, and I will link in the description below to the articles that he's written specifically about the crash of Silicon Valley Bank and other financial institutions.

Finally what I'll say is that I will also invite everyone to check out a show that Michael hosts every two weeks with friend of the show Radhika Desai — they have a show together called Geopolitical Economy Hour, and it's hosted here at Geopolitical Economy Report.

In the description below I will include a link to include a playlist where people can find all of their episodes there explaining the intricacies of economics and geopolitics.

Michael, thank you so much, it's a real pleasure.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well I'm glad we discussed this in a timely fashion, because all of this is unfolding so rapidly that who knows what the story will be next week.

BEN NORTON: Absolutely. We always benefit from this very timely analysis from you. Thanks a lot.

This was an outstanding interview! Please check whether there is a problem with the 'share" settings. I say this because I tried sharing with several people, but they were unable to open it. Error message said something about it being in the form of an "RSS feed" and that the App store needed to be searched for a app that would open it. I hear your podcast via Apple Podcasts, and the link wouldn't work for me on my own phone.