Judicial coup in Argentina: Corrupt judges conspire with media oligarchs to ban Cristina Kirchner from office

Leaked messages show Argentina's corrupt judges conspired with right-wing media oligarchs in a judicial coup against left-wing ex President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, banning her from elections.

(Puedes leer esta nota en español aquí.)

Argentina's notoriously corrupt and deeply politicized judicial system set off an international scandal on December 6, sentencing left-wing former President and current Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner to six years in prison and banning her from future office based on highly dubious charges.

Prominent leaders across Latin America denounced the ruling as a "judicial coup." It is eerily similar to the fraudulent case that led to the imprisonment of Brazil's left-wing former President Lula da Silva in the lead-up to the 2018 elections, which the United Nations Human Rights Committee later denounced as an illegal show trial that lacked due process and violated his rights.

Leaked messages, photos, and videos show that corrupt Argentine prosecutors involved in the case conspired with right-wing opposition politicians, conservative media corporations, and former intelligence officers to wage lawfare (judicial warfare) against Kirchner and her progressive movement.

In a fiery speech following the sentence, Kirchner said the scandal proves that there is a "parallel mafia state" and "mafia judiciary" in Argentina "that is outside of the electoral results."

She added that the legal decision had already been written back in 2019, and that the politically compromised judges were simply waiting for the right moment to use it to prevent her from running for president in the 2023 elections.

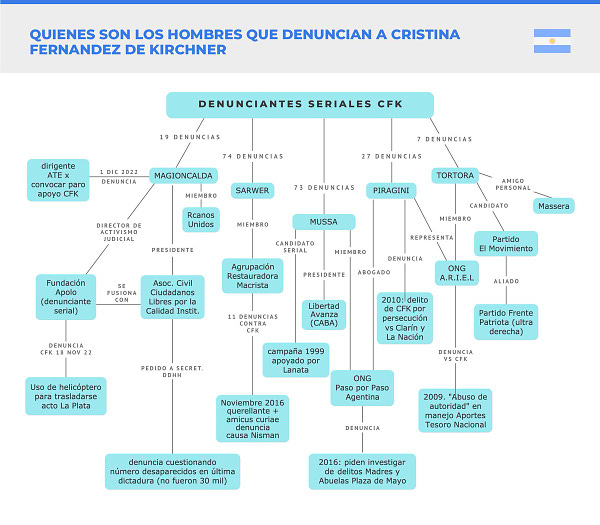

Kirchner had long been targeted in a campaign of systematic legal harassment by the right-wing opposition. She faced 654 legal complaints between 2004 and 2022. Six individuals charged her between 20 and 74 times each. Virtually all of these lawsuits were determined to be totally frivolous, but they drained her of valuable time, energy, and resources.

Multipolarista editor Ben Norton spoke with Argentine journalist Marco Teruggi about the judicial coup.

They also discussed the $44 billion of unpayable odious debt that Argentina is trapped in with the US-dominated International Monetary Fund.

(This interview was conducted in Spanish and was translated into English by Multipolarista.)

Transcript

BEN NORTON: Hi, good morning to everyone, I’m Ben Norton, and today I have the privilege of speaking with the Argentine journalist Marco Teruggi. He is an independent journalist, and also a sociologist.

We are going to speak about the political and economic situation in Argentina.

On December 6, basically, we saw a judicial coup, a judicial coup d’etat, similar to the soft coup against Lula da Silva in Brazil in 2018.

In fact, the same corrupt judge, and ally of the US and CIA, Sergio Moro, who supervised the judicial coup against Lula, and imprisoned him in 2018, he praised the sentence against the vice president of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a sentence of six years in prison.

And clearly, what Argentina’s corrupt and politicized judicial system is trying to ban her from public life, basically, to destroy her public life and her political life.

On September 1, there was an attempt to assassinate her, by a fascist, a gunman from the extreme right wing. That failed. And now there is an attempt to kill her politically.

And according to the sentence, Vice President Kirchner cannot hold public office.

So after the sentence, Vice President Kirchner gave a speech, and in that speech she said that the sentence was already written three years before, in 2019.

She also said that this shows that in Argentina, there is a “parallel mafia state”:

CRISTINA FERNÁNDEZ DE KIRCHNER: As we said on December 2, 2019, that is, exactly 3 years ago, the criminal sentence was already written.

This criminal sentence, this sentence, compatriots, is not a sentence according to the laws of the constitution, or according to the administrative laws, or the criminal code.

This is a sentence that has its origins in a system that I, somewhat naively, that time on December 2, 2019, discussed as lawfare

(judicial war). ... But this is much simpler.This is not just lawfare, or a politicized justice system; this is a parallel mafia state, a mafia judiciary.

And this is confirmation of the existence of a para-state system, of a system where decisions are made about life, and heritage, and the freedom of Argentines, and that is outside of the electoral results.

...

And they, the right-wingers, they left us with $45 billion in debt with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). They ride around in luxury in the planes of Clarín.

...

Well, I am not going to be a candidate. There’s more, very good news for you, Magnetto (director of the Grupo Clarín corporation). You know why? Because on the 10 of December, 2023, I’m not going to have exemptions; I’m not going to be vice president.

So you are going to be able to give the order to your henchmen on the courts and the Supreme Court, that they imprison me, yes. But I will never be your pet! Never, ever! You understand? Never, ever!

I will not be a candidate for anything, not to be president, not to be a senator. My name will not be on any ballot.

I finish the 10th of December, and I will return as I returned on December 10, 2015: to my home.

...

A mafia and parallel state. That is what is happening in Argentina, and that is what today sentenced me to 6 years in prison and a permanent ban from politics.

This is the real criminal sentence; this is what they wanted: a permanent ban from politics.

They will be able to imprison me after December 10, yes. Unless a powerful businessman decides to fund some criminals and, before December 10, 2023, they shoot me.

What do you want? Me as a prisoner, or dead?

BEN NORTON: So, Marco, we should begin with the most basic facts, because this case can be a little complicated. There are many names, there are many people involved.

Can you speak about what is the ‘Vialidad’ lawsuit? This case. And speak about the characters and people involved in this case, because we know that we are not only speaking about judges and prosecutors, but also the Grupo Clarín, one of the country’s most powerful media corporations.

And there is a network of corruption in this case of lawfare (judicial warfare) against Cristina.

MARCO TERUGGI: Let’s start from the beginning, as it should be done.

When Cristina left the presidency in 2015, they started to roll out against her, and against some of the main officials in her government, a series of lawsuits, for different reasons.

Some were clearly fabricated, and with barely any basis, if they even had any.

And there were other, more important public cases, central ones, like this one, which is known as the Vialidad lawsuit, which involves accusations of mismanagement, of diversion of funds for public projects, mainly in the province [Santa Cruz] where Néstor Kirchner, the former president and her husband, had been governor.

So from until today, we have seen a succession of lawsuits, investigations, calls that she appear in court, that perhaps were thought with a certain degree of optimism, that if a government rises to power, like the Frente de Todos government that took power in 2019, that that was going to make it milder, weaker, or at least that they could revert to this plan that was very clearly designed before, as a process of persecution, that they were making through their control of political power.

With the government of the [right-wing former] President Macri, through its control over the media, with a few emblematic groups, like the Grupo Clarín, but also other media outlets like Infobae and La Nación, through intelligence agencies, together with spying devices, wiretapping, monitoring, judicial operations, media operations, and of course powerful economic and media groups, which many times are overlapping.

When [current] President Alberto Fernández took power, that task of democratizing the justice system, that need to dismantle the mechanisms of persecution, well it was an urgent priority, but it was not really carried out.

There are multiple interpretations about that, about why it didn’t happen, why they weren’t able, because they tried to reach a reconciliation, and on the other side [in the opposition] there was no will, because in reality some actors in the Frente de Todos never really prioritized that agenda, because they have some links with the other side.

In any case, the structure of the judicial system was not touched. And what we are seeing now is that system, which was untouched, kept operating as before, as well as the powerful economic interests, mainly the Grupo Clarín, which is the most emblematic in this dispute.

This judicial system that is more and more taken over, from within, by those sectors allied with the opposition, in key places: the Supreme Court, the Council of Judges, the federal courts.

And in turn, there was always a series of underground intelligence operations, which is known as the “crypto-state,” which in this case is operating from outside, but keeps operating.

That kept being rolled out and advancing, until the (sentence on) 6th of December, which was the product of years of spreading the idea that Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was a corrupt president, as well as Néstor Kirchner, as the prosecutor claimed, that they were leading an illegal organization, that is to say, they were claiming that the constitutional governments of Argentina had been illegal organizations.

So what we have witnessed is the media headline that was long awaited by the opposition press, in collaboration with the political opposition, that says: “Cristina charged!”

And in turn, the path toward political banning, in this case it is her permanent prohibition from office, as the judge says.

Although, before entering the next electoral campaigns, according to time estimates, obviously this is going to be appealed by Cristina’s defense team, and that in reality means that she could run in the next elections. But she took the decision not to.

So I think we are at the highest point of a persecution campaign, through various means, against the main political figure of the Peronist movement and the recent history of the progressive movement in Argentina.

And this is proof that there exists something that was known, but which is now very clear: permanent powers that are not elected, which many times do not have recognizable faces, but which operate and shape the reality of countries: economic powers, judicial powers, underground powers, and in this case political powers, like the city government [of Buenos Aires], which is involved in these schemes.

BEN NORTON: Yes, the Latin American Strategic Center of Geopolitics (CELAG) published a graphic that shows that, between 2004 and 2022, there were 654 legal complaints filed against Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. And there are six people who have charged her between 20 and 74 times.

So we are talking about a campaign of judicial warfare, instrumentalizing the judicial system to attack a politician, a left-wing politician.

And Bolivia’s ex-President Evo Morales said it well. Obviously Evo Morales was the victim of another coup d’etat, a violent coup, another coup d’etat in 2019. And Evo wrote that what we are seeing is “a rigged judicial coup that seeks to take away the political rights of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.”

And he also said: “After failing in their attempt to assassinate her, today they try to politically eliminate her.”

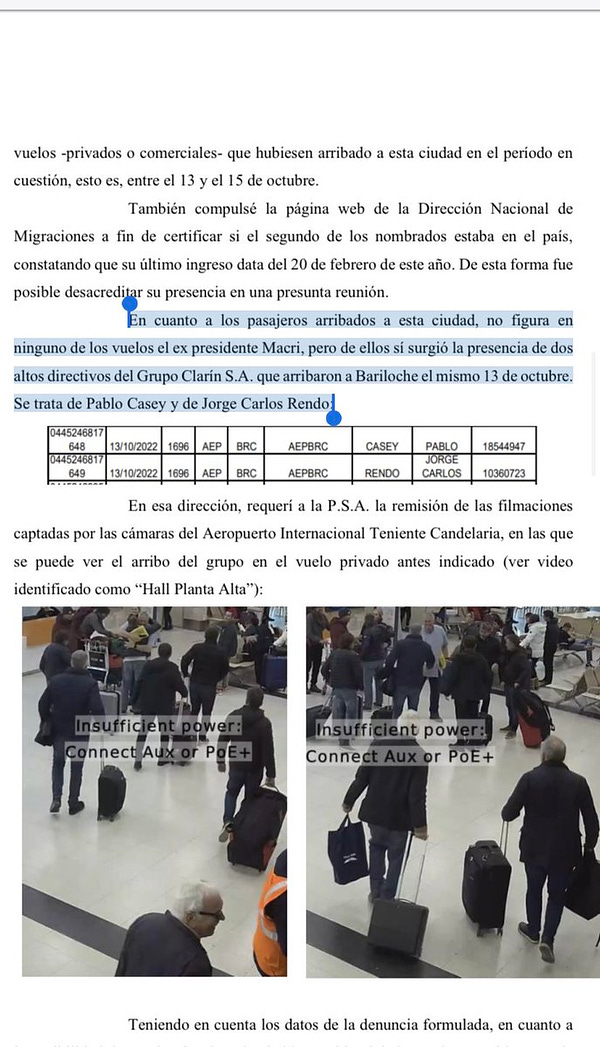

Well, a very important issue in this case, Marco, is that in her speech, following the sentence, the vice president showed leaked messages that show a conspiracy between the prosecutors, officials, and also those media outlets that you mentioned, right-wing outlets that belong to the Argentine oligarchy, in particular the Grupo Clarín.

And there are photos of various prosecutors and officials with members, and not only members but executives of the Grupo Clarín, in the airport.

We know that they flew in their planes, they enjoyed luxurious dinners, very luxurious houses.

So can you speak about the corruption of the judicial system and these prosecutors who are involved in the case against Cristina?

MARCO TERUGGI: The first thing to highlight is that, recently, a few days ago in Argentina, there was a leak. And we have to investigate where it came from, to see if it has any irregularities.

But at least what we see now, and that had not been seen before, is a mechanism by which federal judges work together with the Grupo Clarín, which is a powerful media and economic group, and political sectors, in this case, linked to the government of the city of Buenos Aires, which is the PRO, which is Macri’s party, and ex members of the intelligence services.

Together, in this case what the chats show, is that they were trying to hide the fact that they had met together in the south of Argentina, with the English billionaire Joe Lewis.

In the chat, they directly talk about how to fabricate evidence. It is striking, because it is a federal judge, Ercolini, who in fact is the judge who heard the ‘Vialidad’ lawsuit against Cristina, so we can see who the characters are, who are saying how to make false receipts, among many other things.

Or they talk about how to take down the chief of the airport police, because they think he is the one who leaked the information about them meeting in the south.

And there we see, without a doubt, that the Grupo Clarín is who pays; they organize the agenda; how close all of these actors are.

And therefore we discover the lack of independence of the judicial power, or at least its main actors. The same about the media power.

And the operation of these sectors of above-ground politics and underground politics.

That is a kind of window into what they call the “basements of democracy,” or the sewer, or the place where politics is made, which very few people learn about, and which after is presented by the media as a fact of how the justice system or media work.

So I think it has never been seen before in this way.

And it is an issue of extreme gravity. But it is happening at a moment when those sectors have a perception of themselves, and I think that, shamefully, they are right, of so much impunity.

All of this that has been happening has had a very low judicial and political cost, for actors who, in addition to having left the country trapped in debt, with irregular debts with the International Monetary Fund, some are fugitives, and others have been pardoned by these same judges in the lawsuits brought against them.

So we are seeing a window into real power, that which carries out lawfare operations, that which persecutes people, that which seeks to ban people.

That which raises the rather elementary question, but always necessary to refresh: How democratic is the democracy?

Or what remains of the democracy when the actors who decide a criminal sentence are actors who have not been elected by anyone, who conspire with others, who meet no minimum ethical requirements, or in terms of separation of powers or independence?

BEN NORTON: Yes Marco, you mentioned something very important, which is the subject of the odious debt with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In fact, in her speech after the sentence, Vice President Cristina mentioned this debt.

CRISTINA FERNÁNDEZ DE KIRCHNER: And they, the right-wingers, they left us with $45 billion in debt with the International Monetary Fund.

They ride around in luxury in the planes of Clarín.

BEN NORTON: So Marco, can you speak a bit about Argentina’s debt? The country owes more than $44 billion to the IMF. And this debt doesn’t come from the Kirchnerist governments; it comes from the government of the right-winger, Mauricio Macri, the last president.

MARCO TERUGGI: The government of Macri left two main unpayable debts: one with private creditors, which is larger than the debt with the IMF, and the other of $44 billion with the IMF.

First it was renegotiated with the private creditors, and later with the IMF. Now the main difference is that the debt lent by the IMF, whose main shareholder is the US government, is a debt with a political burden, which involves a mechanism to put a country in a situation of dependency.

That is to say, you don’t negotiate with the IMF only economic concerns, but rather, above all, political and economic ones.

The IMF only approves or rejects debts with economic conditions.

In the first place, we have to say, this debt, when it was given by the IMF, it was above what Argentina could receive. That is, it was irregular in how large it was.

And who was representing the United States? [White House advisor] Mauricio Claver Carbone, in the era of Donald Trump, who later was president of the Inter-American Development Bank.

He said that that debt was to support Mauricio Macri. So it was a political debt, so Macri could continue his government.

So it was always clear, the explicit political support that there was there.

But that is only on the surface, because it seems to me that deeper is precisely that it is debt that, in its essence, is unpayable.

Argentina does not have the capacity to pay $44 billion. So the question is, why would an organization lend a debt that can’t be repaid?

Well, because that debt makes the country enter into a mechanism of dependence, that makes its economic policies, its deficits, its spending, its investments, its social policies, contingent on what the IMF wants, primarily the United States.

So that has been the central part of the tension in the first two years, and in turn in the stronger divisions within the Frente de Todos, when it was announced what the renegotiation of the debt with the IMF consisted of.

Because renegotiating is in reality is a new debt. That is, today Argentina is receiving a new debt, from the IMF, to pay the old debt to the IMF.

That is to say, the IMF regularly supervises Argentina’s economic policies and if they like them, they give them the money, so that it can be returned to the IMF.

And if they don’t like them, they could refuse to give Argentina the money, and Argentina would default.

We are on that level. And it seems to me that we have to recognize that the mechanism worked.

Today it is a government that is conditioned, that in large part has its hands tied in its economic policy, with inflation that it can’t reduce, with a loss of purchasing power.

And there is a problem with the restriction of the entry of dollars into the reserves of the central bank, which among other things is largely because it has to regularly go to return the money to the IMF.

So I think that is a clear example of how these debts function, why they are made, how they force governments to make concessions.

BEN NORTON: You mentioned that there are economic problems; there is inflation. In fact, in her speech, following the sentence, the vice president said that, “They condemn me because they condemn a model of economic development.”

CRISTINA FERNÁNDEZ DE KIRCHNER: I speak fundamentally about us, from Peronism, those of us who are committed to the rights of the people, that is where they are sentencing me.

They condemn me because they condemn a model of economic development and of recognition of the rights of the people. That is why, that is why they condemn me.

But the sentencing is not only six years in prison. The real sentence against me is the permanent ban on holding elected public office.

When all of the positions that I held always were by popular vote. We won four governments in the name of Peronism, with the last name Kirchner, in 2003, in 2007, in 2011.

And I also contributed to the victory that we had in 2019, when no one would have bet on Peronism.

This is what they are making me pay. This is why they are banning me.

BEN NORTON: So can you speak about the economic situation, with the inflation, and why do you think there are so many economic problems?

MARCO TERUGGI: In the case of Argentina, we are in a situation of weakness. It is a government that has spent so much recent time trying to survive the crisis, that has implicitly or explicitly rejected the possibility of transformation.

It is in a sense the great loss of political, symbolic capital. Cristina is losing a lot of political, symbolic capital, because in her memory, her governments were different.

And the current situation, well, is of a country with a very high structural level of poverty, whose workers’ salaries are below the poverty line, and more and more difficulties.

But in economic terms, what are the concrete, material agreements that can be made to alleviate the political situation in Argentina, for example to give it more international reserves, greater capacity to strengthen its policies as it faces an election?

This is quite decisive. If a government arrives with inflation that is not significantly reduced, that arrives cutting social spending, the fiscal deficit, but it does it by cutting from below, it is very unlikely that it has the chance of electoral victory.

I think that, in a way, we are in a scenario that has the Latin American dynamic, when it seems that a majority group of progressive governments are finally going to be able to coordinate together, we see how some win while others are undone.

Peru’s President Pedro Castillo was just forced out, as the consequence of another very deep institutional crisis.

And finally, to conclude, one thing about the external restriction of dollars: There is the issue of the external debt, which effectively is a permanent drain of dollars.

Another debate is how Argentina can get dollars, through what economic mechanisms?

And there a lot has to do with the agricultural export sector, which is a sector that historically is opposed to the Peronist governments, or at least against Cristina’s governments, and this one.

And that is a sector that lobbies for the devaluation of the currency, which has a negative impact on the population.

Because a devaluation in the currency implies an increase in the prices, implies a loss of purchasing power.

So the government has been giving in, giving them a preferential dollar, as they say, so they have more incentives to bring their dollars to Argentina.

But we are on that level. And it also has to do with the economic structure of Argentina, with the conflicting models.

What is the model that they want to build in Argentina?

And there, Macrismo is very clear what its model is: it is a neoliberal model, financial, of opening up the economy, that has brought the catastrophic consequences that were produced in just four years, in which they were in power in the Pink House.

BEN NORTON: Thanks a lot. I have been speaking with the Argentine journalist Marco Teruggi. You can follow him on Twitter at @Marco_Teruggi. Marco, thanks so much, I’m always grateful for your journalistic work and analysis.

MARCO TERUGGI: Thank you, and I send a big hug from Buenos Aires.