How can BRICS de-dollarize the financial system?

BRICS plans to transform the international monetary and financial system, and debated policies at the 2024 summit in Kazan, Russia. How can it challenge the dominance of the US dollar?

BRICS plans to transform the international monetary and financial system, and debated potential policies at the 2024 summit in Kazan, Russia. Can it successfully challenge the dominance of the US dollar?

To discuss BRICS’ proposals, political economist Radhika Desai is joined by Ben Norton and former central banker Kathleen Tyson, author of the book Multicurrency Mercantilism.

You can find more episodes of Geopolitical Economy Hour here.

Video

Podcast

Transcript

RADHIKA DESAI: Hello and welcome to the 35th Geopolitical Economy Hour, the show that examines the fast-changing political and geopolitical economy of our time. I'm Radhika Desai.

So, the BRICS summit in Kazan is over. A communiqué has been issued, and as usual, commentators are dividing between those who overstate and those who dismiss what has been achieved.

The West prefers understating the achievements, pointing to important differences that undoubtedly exist among BRICS countries. They prefer to portray BRICS as fractious, directionless, and indeed vainglorious.

BRICS boosters, on the other hand, are busy touting every little statement of intent as an accomplished fact, each marking a major milestone on the path away from Western dominance.

Rather than giving in to these equal and opposite temptations, we tread a different path, one that is closer in spirit, at least, to the boosters but considerably less inebriated than they seem to be.

There is absolutely no doubt that the inherited institutions of international economic governance, which have long been inadequate to the developmental purposes of the overwhelming majority of the countries of the world, as we've seen from decades, indeed, of organizing among third-world countries against them, once culminated in a demand for a new international economic order.

So we've seen that these institutions are inadequate to the developmental needs of the countries of the world, and they're increasingly opposed, rejected, and criticized by the world majority countries, to use the Russian nomenclature.

These countries find their interests not represented by these outfits, whether it is the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO, and last but not least, the vast paraphernalia of the basically privately-owned institutions that still run the world's money.

While these institutions are in many ways in crisis, the internal structure of power relations in practically all the BRICS countries are reigning in advances toward alternatives because their objective interests still seem to align with the dollar creditocracy—the private institutions that run the world dollar system.

Though we recognize this — we are clear about that — we also understand something else that puts clear blue water between ourselves and those who dismiss the BRICS. That something is an understanding that both pull and push factors are leading the BRICS, and through them the world, away from the decaying, productively enfeebled, financialized, and innovation-hobbled West and towards China, which is rising in all these respects, and the other BRICS countries that have a chance to do the same if they learn, like China, to control corporate power.

This is the recognition we bring to today’s discussion. So, who are we? I'm joined today by our very own Ben Norton, the host of the Geopolitical Economy Report website on which the Geopolitical Economy Hour show is regularly hosted. Welcome Ben!

BEN NORTON: It's a pleasure, Radhika. Thanks for having me on your show.

RADHIKA DESAI: And we also have with us a very special guest, Kathleen Tyson. Kathleen Tyson is an expert on the international monetary and financial system. She started her career at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, where she was a founding member of the Settlement Systems Studies Group. She then moved to London to supervise global securities markets and international central securities depositories, Euroclear and Clearstream.

She is the author of a very important book on the subject of the end of dollar dominance, called Multicurrency Mercantilism: The New International Monetary Order, which came out just a year or so ago. The book is about the transition away from the unipolar dollar world.

So, welcome, Kathleen. It's a great privilege for us to have you on our show.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Thank you, Radhika.

RADHIKA DESAI: So today we want to discuss a very important and interesting document put out by the Russian government. It has been put out by the BRICS Chairmanship Research, which is presumably the research arm of Russia's chairmanship of the BRICS in 2024, and it is entitled Improvement of the International Monetary and Financial System.

As everybody knows, the Russian government has been at the forefront of countries that would like to see de-dollarization, its enthusiasm has led to a critique of the dollar system in this report that is more profound than practically any seen in official documents produced by various BRICS governments.

On the other hand, while many of the solutions this document proposes are very well considered, others remain problematic, precisely because they tend, as is the want of most governments, to concede too much to markets and private power.

We will be arguing that while we support the thrust of the criticisms, which point in a markedly progressive direction, we also realize that these governments, as embodied historical actors, are—since they embody the legacy of the 40-plus years of neoliberalism—still some way from recognizing what really needs to be done.

We make this argument confident in our understanding that the present direction of the West is not the way to go.

While the BRICS must aim at productive, dynamic, innovative, exclusive, and egalitarian economies, that is not the direction in which Western economies are going.

So let me put an end to this very long introduction and ask Kathleen to perhaps start us off with some overall remarks about how she reads the report and what she sees as its significance. Kathleen, please go ahead.

KATHLEEN TYSON: OK. Thank you. Just to preface this, I have a foot in both worlds. I built most of the capital markets infrastructure that runs the current global financial system. I'm proud of that, and yet I also recognize the challenges, the instability, the critical vulnerabilities, and the need for other countries to rise without being constantly threatened with destabilization. So, I really have a foot in both worlds right now, trying to keep friends in both worlds too.

I did read and summarize the report. The key takeaways I'll just summarize for me, though other people will read different things into it. But the big one was no new currency. All of the delusional hyperventilation about a BRICS currency—it's just that, it's delusion.

The Johannesburg declaration last year was perfectly clear that the BRICS want local currency trade in their own currencies as the preferred objective. And to a great extent, they've achieved that in important ways.

For instance, 53% of China's trade is now in yuan, and over 90% of trade between Russia and China is either in yuan or ruble. Other countries are making progress as well—80 countries determined in 2023 to move to local currency trade as a matter of policy.

So, it’s not just BRICS. I mean, I said this last month in Singapore, and I think it resonates, that currency optionality is now a matter of economic and national security. No country wants the constant threat of dollar sanctions hanging over them, their corporations, and their future prosperity.

Southeast Asian states have unanimously agreed to move to local currency trade. They're not in BRICS, though some of them will be next year—three of them, in fact. They made that decision in their collective self-interest.

So, it's part of a global movement towards currency optionality, which is really underpinned by the need to get away from the constant threat of sanctions. That was a big takeaway for me.

There’s no new currency, no gold-backed currency, no commodity basket currency, and no crypto scheme—just good, old-fashioned dealing in domestic payment systems that already exist.

Beneath that, other important points from the report include that the core principles of the new monetary and financial system should be security, independence, inclusion, and sustainability. I don’t think anyone can object to any of those.

They have not agreed on a new multi-currency payment system, but they’re working on parallel developments as alternatives to the SWIFT messaging platform, and they’re working on domestic payments interoperability.

In the past year, there have been a few instances of bilaterally linking domestic payment systems to ease cross-border payments. Russia has proposed that BRICS central banks create supranational infrastructure for a common settlement platform, though this is not yet agreed upon.

The BRICS Kazan Declaration, at paragraph 66, mentioned that they want to do further work on cross-border payments and have delegated this back to the central bank governors and ministers of finance to report next year.

Building global infrastructure, from my personal experience, is not simple, and I can see where they're tripping up and the challenges they're facing. This isn’t unique to them either.

This week, the Bank for International Settlements, at the IMF-World Bank meetings in Washington, tried to introduce a multi-currency payment system, but the members declined it. So, these challenges are complex, and achieving buy-in is difficult to create organically because there’s always suspicion about new infrastructure.

Now, here’s something I like: Russia proposes BRICS Clear. This is news. It’s the first time we've seen BRICS Clear.

Essentially, Russia had $300 million of its assets frozen in 2022 in Euroclear, and then the proceeds were seized and given to Ukraine—expropriated, or securitized, however you want to frame it. Russia has been denied access to many assets and proceeds.

So what they're trying to do with BRICS Clear is to break the Euroclear-Clearstream duopoly. Collectively, Euroclear and Clearstream hold about $50 trillion in assets in their depositories. BRICS Clear aims to create a securities depository for BRICS assets, independent of this duopoly.

Full disclosure: I was Deputy General Counsel and Deputy Company Secretary of Clearstream, so I’m very familiar with the governance challenges they're likely to face.

For instance, the first principle for financial markets infrastructure is legal certainty. Which jurisdiction are they going to put this new depository in? It can't be Russia, because of the 14,000 sanctions in operation and because executives have a bad habit of falling out of tall windows there. It can't be China, because India would object to more Chinese dominance over global financial infrastructure. And it likely won’t be South Africa, Brazil, or India because there will be lack of confidence in non-discriminatory commercial law. So, where will they put it?

That's just one of the many principles that have to be addressed to successfully build new infrastructure.

BRICS Clear is news. I’m particularly interested in the challenge of it, having a background in depositories and in clearance settlements and securities finance. It would be great thing to have. I’m just not sure where they are going to put it and how they are going to put it. I suspect they are not either because they didn’t even use the phrase ICSD in describing it.

So just the capacity development that’s involved and even detailing the feasibility study agreed in the declaration that it is a big challenge.

They have called for reducing reserves in U.S. dollars and moving towards alternative reserves.

They want an urgent review of funding vulnerabilities in emerging markets, and reform of the IMF and SDRs, which they see as inconsistent with modern needs.

Some measures they’ve tried to implement, like the BRICS credit rating agency, are proving problematic and not meeting their intended purpose.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, that was an excellent overview, Kathleen. Thank you.

I do want to say, by the way, that it's a real pleasure speaking with you about this. I feel like we're all privileged because it's so rare to have, you know, someone from the inside—a financial plumber, if you will—who helped design these systems, and is also dedicated to creating a more equitable framework. Because, I mean, you can understand better than all of us the problems that exist within these systems.

I want to reference an excerpt from your book that you actually tweeted out after reading this report. This is from your very interesting book, Multicurrency Mercantilism, which everyone should go out and buy.

In this book, you argue that the transition to multicurrency mercantilism will be gradual, and you point out that, in some ways, it's kind of easy to de-dollarize global trade. But de-dollarizing the financial system overall is much more complicated.

You point out in your book that global trade in goods in 2023 was approximately $46 trillion, about half of which was in U.S. dollars. So de-dollarizing $23 trillion is not as ambitious compared to the other parts of the financial system.

This is modest compared to global finance, where bonds alone represent over $307 trillion in par value.

KATHLEEN TYSON: It’s a lot more now.

BEN NORTON: Exactly, with so much debt growing in the United States—120% of GDP in federal debt, and 6% of GDP in deficits per year.

But you also point out that the entire market capitalization of equities around the world is $108 trillion, which is about five times all of global goods trade in one year.

Derivatives alone have a notional value of $635 trillion.

And in the foreign exchange market, it’s nearly $2,000 trillion. It sounds like a joke, but in the foreign exchange market alone, there are $1,900 trillion in settlements every year.

KATHLEEN TYSON: I know. I don’t even know what foreign exchange trade is about because, when I engaged to build CLS Bank, the total foreign exchange daily transactions were about $830 billion. And now, every single day, CLS settles an average of $7.5 trillion in just 18 currencies. These are enormous numbers.

And when you think that all global trade annually, excluding the dollar, is $23 trillion, it’s ridiculous that there’s that much foreign exchange sloshing around.

But there it is—that's the system I built, and it works.

BEN NORTON: It’s an incredible quantity we’re talking about.

So, you point out that capital markets will still be dominated by dollar-denominated instruments. However, I wanted to highlight that, while de-dollarizing global trade is much easier than de-dollarizing capital markets, it’s also more important, right?

Because the vast majority of these financial flows—like derivatives—don’t really impact most average people. Now, if all those bets collapse and cause another financial crisis, that will impact people.

But, at the end of the day, China and Russia aren’t as concerned with de-dollarizing the global derivatives market or other bond markets.

Their main concern is securing their ability to pay for imports in their own currencies. China just wants to buy oil and gas in renminbi without needing access to dollars.

They’re focused on their domestic bond markets too. Especially since the People's Bank of China has been reducing its holdings of U.S. Treasury securities for a decade now.

It’s quite reasonable to suspect that countries can, over the medium term, de-dollarize what’s most important to them. The rest of the capital markets can stay in dollars, but is that really a big issue for the BRICS countries?

KATHLEEN TYSON: Right, there was an announcement in the report from both the improvement to the international monetary and financial system and in the BRICS declaration that they are exploring setting up hubs.

There’s a difference between the two, by the way. In the international monetary and financial system report, the Russians proposed setting up regional hubs for trading oil, gas, gold, and grain. But the BRICS declaration released after that only suggests setting up hubs for grain trade.

BEN NORTON: Although they said it could expand to other commodities, but they're starting with the grain exchange.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yes, they're starting with grain, and most of them already have gold exchanges in their countries. Moscow has a gold exchange, Shanghai has a gold exchange, and Dubai has a gold exchange, so maybe they just don’t need more gold exchanges because they already have them.

But setting up grain exchanges for trading grain in local currency would be a significant force in stabilizing grain prices in emerging markets, where unstable prices and agricultural imports often drive underdevelopment. So, that is actually a big, big signal event.

Russia itself is responsible for 28% of global grain exports—well, that’s wheat exports. They also export large amounts of other things: soybeans, barley, and other grains.

So, Russia moving to create hubs for grain trade in the Global South to stabilize food prices for that region would actually be a huge win for sustainablity and equitable development.

BEN NORTON: Kathleen, you made very interesting points, and I agree. What I'm curious about is that I don’t think the BRICS countries necessarily care about de-dollarizing capital markets. They don’t care if the U.S. financial system has all of these hundreds of trillions of dollars in derivatives, as long as it doesn’t destabilize their own financial systems.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Exactly. And, you know, one reason China continues to be a closed economy and is cautious about allowing Western financial institutions in—though they have liberalized significantly—is because they do not want to be destabilized by vulnerabilities that persistently cause crises in the West, whether it's dodgy securitization, dodgy credit ratings, or dodgy derivatives that can destabilize pension funds, as we saw in the UK two years ago.

They are cautious about importing those kinds of problems and rightly so. As a former market supervisor, I feel uncomfortable with the risks that we're currently running.

RADHIKA DESAI: Yeah. So, you know, I just wanted to intervene here because I think the point you raised, Ben, about the difficulty of de-dollarizing capital markets versus the ease with which we can de-dollarize trade.

This is actually connected with a couple of the points that Kathleen picked out when she was enumerating some of her main takeaways. I think they are very deeply connected, and I just want to highlight them because that also connects this conversation to the legacy historical discussion that Michael [Hudson] and I have had on de-dollarization over the past couple of years.

The two points I want to refer to are, Kathleen, your first point that you are very glad they’re not proposing a new currency, this is not the way to go, and they are working on existing national currencies.

Our argument, Michael [Hudson] and I have always maintained, is that this aligns with Keynes's original argument. At Bretton Woods, when he presented his proposals regarding the International Clearing Union and a Bancor, he argued that if there were to be any single currency replacing the existing multi-currency order—which, yes, the dollar may be dominant, but it is not the only one—it would be a currency that is not an ordinary currency that we can use to pay for a restaurant meal or buy a bar of chocolate. It would be a currency for use within international banks, settling imbalances between banks periodically, and so on.

So, no new currency is a good thing. The reason no new currency is beneficial is that the fundamental premise of the dollar system has never been problematized, except by people like me in Geopolitical Economy, and later in my writing with Michael [Hudson]. A national currency has never been stably and securely the currency of the rest of the world.

For example, Britain’s sterling was only able to be a world currency because it was not a national currency; it was an imperial currency that could swing surpluses derived from the rest of the world as liquidity into the international market on a grand scale for those times and those proportions that were involved.

The United States dollar, having no capital to export in a completely different era, when you could not afford the kind of industrialization that Britain took upon itself, which the United States eventually inflect upon itself.

Nevertheless, the United States dollar could not export capital in the immediate post-World War Two period; it could only incur deficits to provide liquidity. Triffin pointed out a long time ago that this was inherently contradictory. The more liquidity you provide, the less attractive your dollar becomes, and that phase ended when the Europeans said, “You folks keep your valueless dollars; give us gold”.

What happened next was that after the U.S. took away the gold backing and refused to exchange any more gold for dollars, the U.S. financial system saw many boosters pretending the Triffin dilemma disappeared. But no, there has always been a Triffin dilemma.

The way it has been addressed is by countering the downward pressure on the dollar that U.S. deficits inevitably exert—trade deficits, current account deficits, fiscal deficits—all of these things exert downward pressure on the dollar, which has been alleviated by the inflation of successive financial bubbles.

There has been vast expansion in dollar-denominated financial activity, which has nothing to do with trade, which is why it is easier to de-dollarize trade. That’s the first point I wanted to make.

I also wanted to say I liked your summary because this is deeply connected. Just bear with me for a second.

I liked your summary of the main points, but I want to add one more thing, and that is the report is very aware that the existing dollar system leads money to flow from what they call emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) to the advanced countries.

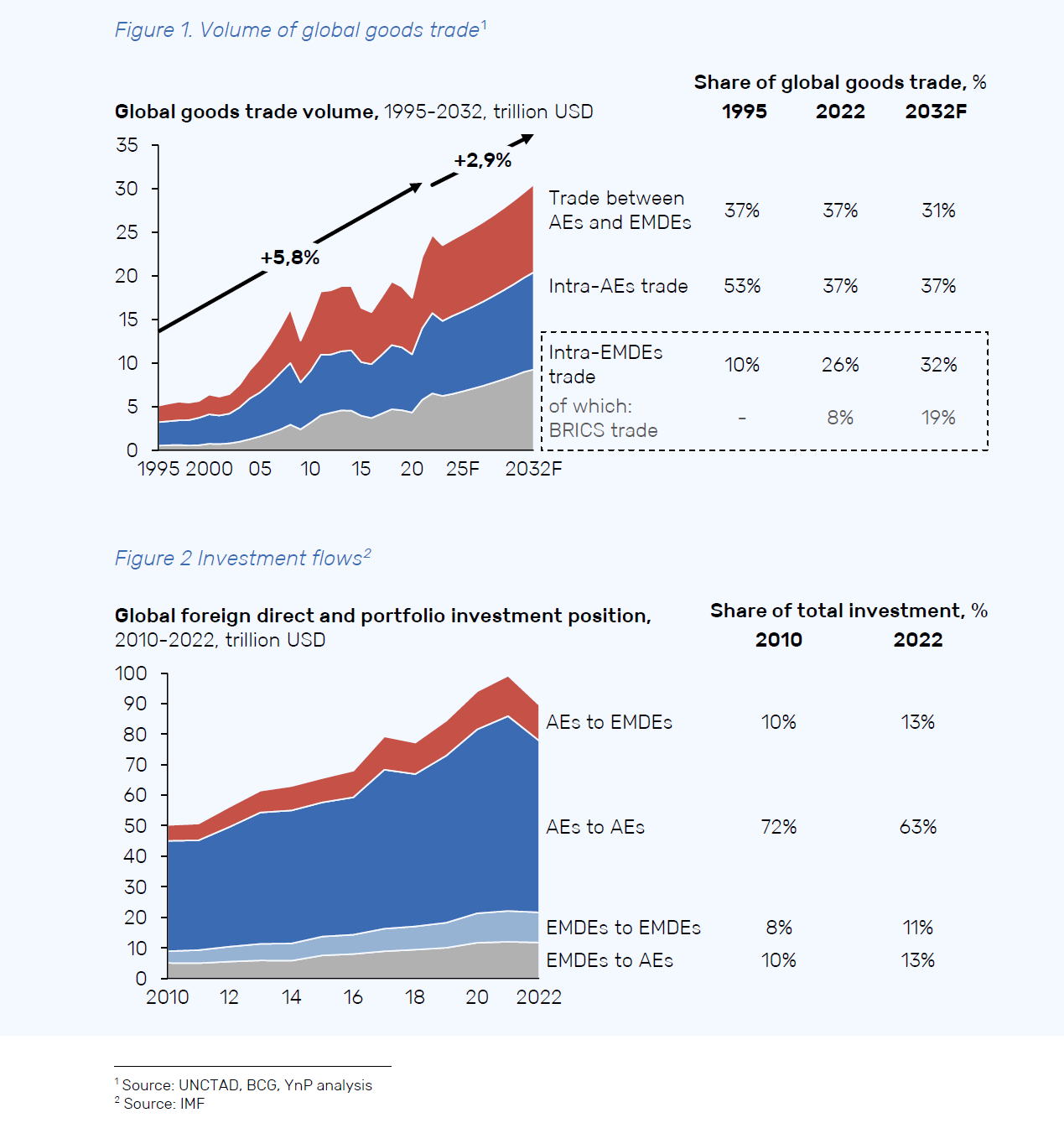

I want to show you this one chart, which I think is a good one:

So, they show this chart, which indicates that contrary to what most people worry about—jobs being lost in first-world countries—most foreign investment, and these are stocks, not flows, actually comes from AEs to AEs. The big blue section indicates this.

A small amount goes from advanced industrial countries to emerging and developing economies, but here's the one these people are worried; and an even smaller amount goes from emerging and developing to other emerging and developing economies.

But this is the one they are concerned about the most: about 10 to 13%, with the most recent figure being 13%, actually goes from the emerging and developing economies into the first-world economies.

This is essentially the situation they’re complaining about. How do you create an international financial and monetary system that avoids this?

My simple answer, which I want you both to comment on, is that the only way to do it is some version of capital controls. You can call them something nice like capital account management or whatever, but some way of essentially corralling the capital in your country and obliging it to be invested productively in your own country is the only way to go.

KATHLEEN TYSON: OK, well, I’ll start on that one. I’m not a big fan of capital controls, but I would be a big fan of localizing the sale of natural resources and agricultural output—industrialized plantation-style agricultural output—into local currencies as a means of avoiding the two-tier pricing of the current system. In that system, they virtually pay pennies in the local economy and offshore price it somewhere else where the price is much higher.

If they can localize the sale of their locally produced goods and resources, they will capture much more fiscal stability and it will be in their own currency, free from the instability of offshore dollar pricing, which by in large never comes back to the local economy.

For instance, in Nigeria a few years ago, the central bank ordered two container ships full of cocoa to be impounded until the proceeds were paid locally. They knew that if those ships left, not a penny of the cocoa would come back to the country, and they needed the cocoa revenues to service the World Bank debts that funded the corporate plantations.

RADHIKA DESAI: But wouldn't it be that, supposing you localize it—by which you mean that Russia should sell oil and gas in its own territory, more to the point in rubles—if there are no restrictions on converting rubles into foreign currency, wouldn’t some of it leak out of the Russian economy?

KATHLEEN TYSON: Some of it has to leak out if they're going to buy the things they need. The question is whether it's realized in-country at all. They have to be an attractive venue for investment, which requires some openness. Well, I don’t think that it does.

There are various requirements in each country, and there needs to be recognition that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. China has done, wouldn’t be suitable for South Africa.

RADHIKA DESAI: Right, although, at some point, I would say the amount of liberalization you have to undertake to attract investment may be judged to be too great.

If you consider that foreign investment for most countries constitutes a relatively small portion of total gross fixed capital formation, the situation is different now. Companies like Walmart are not investing elsewhere; they’re asking entrepreneurs in other countries to invest, creating supply relationships with them. In that sense, it’s outsourcing rather than FDI that is the dominant paradigm of the so-called internationalization of production.

Given that about 80 to 90% of investment in any country is typically domestic, is it a huge cost to pay?

Back in the day, when most countries still had capital controls, if a company wanted to invest in Chile’s copper or Russia’s gas, they would have to come in because the resources can’t be moved.

KATHLEEN TYSON: There are still capital controls in most countries.

RADHIKA DESAI: Yes, that’s true.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Let’s be honest; one reason why African states don’t trade with each other is because of the horrific mess of capital controls in most African states. They trade with each other through the euro or the dollar because they can’t trade with each other in their own currencies. That’s a factor of each of them having horrendous capital controls.

From a client in Africa, I had one who defaulted because they couldn’t pay me, citing capital controls. The capital controls themselves are a huge constraint on development. I don’t think that’s the answer.

RADHIKA DESAI: Okay, I would just say, though, that the lack of trade between many countries in South America and Africa is often more about the similarity of productive structures.

If both countries are exporting cocoa, they’re not going to trade with one another. You need to create greater trade complementarities, which is going to be a longer process. It’s not going to happen tomorrow.

I’m sure they’re not the greatest designers of capital controls, and that’s an independent problem as well.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yes, well, there are many problems to solve out there. How do you choose which ones?

The objectives and priorities have been made clear, and they’re taking a very sensible, measured course of development.

I think the grain hubs will be interesting to watch because Russia is such a dominant producer of grains, and because the others are all big importers. Well, India is also a huge exporter of grains.

We’ll see how that initiative goes and whether it expands, as that could rationalize and bring down inflation in many vulnerable countries.

BEN NORTON: Kathleen, you mentioned the issue of BRICS not trying to create a common currency or unit of account in the short to medium term.

You also mentioned that in the report written by the Russian BRICS chairmanship, they called for strengthening the SDRs, the Special Drawing Rights.

For people who don’t know this, SDRs are an international unit of account overseen by the International Monetary Fund. It’s essentially an international currency, not dissimilar to the idea that Keynes proposed with the Bancor and the value of the SDR is based on a basket of five currencies at different weighted values that change over the years, which are the dollar, euro, Japanese yen, British pound, and Chinese renminbi.

What’s interesting is the report states that the SDR has several issues now. For instance, they can’t be used in the market; they’re only a unit of account administered by the IMF.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Its an alternative reserve. They can’t be spent; they are not a currency.

BEN NORTON: Exactly, but what’s interesting is that, in the report, they call for new infrastructure to be developed so the SDR could actually be used in market transactions.

This essentially represents a step toward creating some kind of unit of account that could be used to settle trade imbalances, backed by a basket of currencies.

I’m wondering if you could elaborate on the strengths and weaknesses of this idea.

We’ve discussed the de-dollarization of global trade, which, as you point out in your book, is relatively modest compared to other changes. The other challenge is not only de-dollarizing trade but also de-dollarize savings, right, de-dollarizing reserves held by central banks, and this could be a reserve asset.

In fact, the report also calls for creating new financial instruments denominated in the currencies of BRICS members, strengthening bond markets. Instead of having eurodollar assets denominated in offshore dollars, they’re calling for selling these assets in the currencies of BRICS members.

It might be difficult to convince investors to buy those if there are exchange rate risks, but the SDR seems like it could be a way to address that issue. What do you think?

KATHLEEN TYSON: I’m a lifetime skeptic on the SDR, particularly after the last re-weighting. To me, any basket is prone to manipulation by the incumbents, and that’s what we see with the SDR. Initially, they kept changing the formula, and now they’ve abandoned the formula altogether.

In 2015, when they admitted the yuan as one of the currencies, they established a formula approved by the IMF Board that weighted the SDRs according to their use in financial markets and exports – two factors.

If they had applied that weighting in 2020, sterling would have fallen out of the SDR, because it has lost its export market. Our biggest export market was the EU, and it doesn’t take our products anymore.

In terms of capital markets, sterling is now insignificant. Nobody needs it for anything. It has legacy use in some Commonwealth transactions, but that’s it.

Instead of rewriting it using the formula in 2020, they pled pandemic and delayed the waiting for two years. Then, in the dark of night, with no fanfare, they announced a new weighting of the basket without any explanation of how they arrived at it.

RADHIKA DESAI: And of course, what you're also saying is that this will never serve the purpose unless the IMF itself is reformed in a big way.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Well, yes, and it’s interesting that you bring that up, Radhika, because I just did a search on the Kazan Declaration, and it doesn’t even mention SDRs. So clearly, that was one Russian proposal that’s been kicked back.

Yes, of course, the IMF governance is completely out of date, and the SDR is not fit for purpose anymore.

But again, it’s very difficult to address that as long as the IMF is based in Washington and operates as a huge redistributive mechanism for global wealth.

RADHIKA DESAI: That’s a really interesting point. It leads me to another question I’ve been wanting to ask you, which is about the proverbial problem regarding the use of national currencies in international trade.

Some countries end up with unusable stocks of another country’s currency—Russia stockpiling rupees is a typical example.

How would you see that problem being resolved? Would it require the creation of some kind of unit of account that enables multiple clearing?

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yes, that’s a good question. I would say we’re returning to gold as a hegemonic asset. Central banks bought at record rates in 2023, and accelerated purchases in the first half of 2024.

So there is a money for interstate settlements called gold, which worked for 3,000 years. We had a 50-year hiatus where we switched to dollars, and that hasn’t worked out very well. Now we’re going back to gold.

But gold isn’t the only asset. What’s interesting to watch is if these grain hubs expand to oil, gas, and gold. Then you have alternative barter currencies that you can stockpile if you have a currency that you don’t want to hold.

RADHIKA DESAI: No, this is very interesting because, of course, Keynes, who is known for calling gold a “barbarous relic”, did, however, say that the value of his Bancor would have to rely on a basket of, at that time, he enumerated some 30 most highly traded commodities.

Commodities are very important because, while gold has a certain special function, prices are generally affected by the prices of primary commodities. This is our encounter with nature, which is always less predictable than our encounter with our fellow human beings in manufacturing. That’s why there can be so much fluctuation in the prices of primary commodities.

Keynes said that the weighted average of 30 of the most traded commodities should form the basis of the value of Bancor. I think which commodities become interesting, but the BRICS countries can easily set up a working group that identifies an inclusive set of commodities whose prices affect everybody to some roughly equal extent.

They could then say, “OK, we will base the currency reserve or the currency unit of account which we will use for mutual transactions on this”.

Do you think such a thing could happen?

KATHLEEN TYSON: No, I don’t think there would be global agreement on that. I don’t think there would be consensus even within BRICS.

What we’ve seen is that the Russians recommended hubs for oil, gas, gold, and grain, and the only one being implemented in the declaration is for grains.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, but it also says they can expand to other commodities; they’re just starting with grains.

KATHLEEN TYSON: No, that’s a fair point. But especially given the unequal distribution of resources and the way they’ve been historically exploited—where resources are extracted from emerging markets, the Global South, and the Global East, with the profits going to London, New York, or Chicago—that’s really the nub of it.

By moving to local currency trade and creating their own pricing nodes through these hubs for the things that concern them most, like grains, energy, and gold, they can equalize and make accessible more equitable exchange and stabilize inflation. That would be a huge win for them.

Most states would benefit; I mean, China has had near-zero inflation for the longest time and hasn’t had a single quarter of negative growth since 1986. China’s hacked stability and that is really what they’re trying to export is stability.

RADHIKA DESAI: Although, you know, I can understand that Keynes’s plan would have, of course, reflected British interests. His advisors were always British, advocating for British interests.

Keynes was speaking for a country that has historically relied on importing practically all its natural raw materials and other inputs, and he is concerned about stabilizing import prices for Britain in particular.

But a grouping like BRICS -- which, as you know, Jim O'Neill originally coined the term to include what he called the two natural resource-intensive economies, Brazil and Russia; and the two really big human resource-rich countries, China and India.

You’re looking at the interests of both exporters and importers, trying to come up with some kind of balance between those two, so you can give a decent price to exporters while stabilizing and not fleecing the importers.

Do you think that, despite that, it will be difficult to come to some sort of agreement? Is the goal still to remain the fallback position?

KATHLEEN TYSON: The risk of any basket is that, as soon as you give bankers a target for manipulation, they will manipulate it.

RADHIKA DESAI: You mean central bankers will manipulate it?

KATHLEEN TYSON: Both central bankers and commercial bankers, mercantile bankers—every kind of banker.

If you give them a target, a single node of vulnerability, they will target that for destabilization because they make money out of destabilization.

RADHIKA DESAI: Of course, you could bring back some version of Glass-Steagall, which prevents the overwhelming majority of banks—this would be in all countries, not just in the United States—from doing this sort of thing.

RADHIKA DESAI: Well, I think Paul Volcker called for that after the great financial crisis. He called derivatives “weapons of financial destruction.” I’m very sympathetic to that.

RADHIKA DESAI: Indeed, he did.

KATHLEEN TYSON: In my early career, I was on the team that overturned Glass-Steagall, and I was on the team that liberalized derivatives. Now, with mature perspective, I think both were misguided.

RADHIKA DESAI: Well, I mean, overturning Glass-Steagall really opened the floodgates to the 2008 housing and credit bubbles. Those bubbles wouldn’t have worked in 2008 without that.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Twenty, twenty-three years later.

RADHIKA DESAI: No, sorry. It was less than a decade because it was repealed in 2000 and it was repealed in 1999. By 2008, we had already had the bubble, and it had already crashed.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yeah, I think there are slightly different issues, but certainly by structurally combining mercantile banking and over financialization, the entire real economy becomes vulnerable.

This is what China avoids. Whenever it sees too much excess financialization, it curbs it through the state-owned banks and keeps reinforcing the policy that they support the real economy.

RADHIKA DESAI: And you know, this is so widely misunderstood. I mean, the number of commentators going around talking about China’s property bubble being the same as the American property bubble that burst in 2008—sorry, folks, it’s not the same.

The people who are in trouble are not the banks; the people in trouble are the developers. The government is doing everything possible to save the ordinary homeowner.

If you look at all of these things, the whole situation is completely different. But it doesn’t prevent people who should know better from saying this kind of thing. It’s astonishing.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yes, I think a lot of Western countries would like to have a crisis with 96% home ownership.

RADHIKA DESAI: Would love it, yes.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yeah, 80% without a mortgage, yes.

RADHIKA DESAI: Well, that’s the thing. In China, people rarely buy with a mortgage; people buy with their savings.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Because they save. It’s a culture that values saving. But yeah, I think that’d be a great crisis to have. It’s not the way we do crises.

RADHIKA DESAI: No, and the thing is, sorry, just one final point I wanted to make is simply that China doesn’t have these problems precisely because it has a system that has, you know, not exactly Glass-Steagall, but rules pretty similar to that, aimed at keeping the financial system investing in the productive economy and not speculating in financial markets.

Which kind of brings us back to our original point, which is that we are living in a dollar system that is reliant on regular inflation and, therefore, inevitably, of course, on regular bursting of financial bubbles. This is also why the world could not afford it.

I must say that I was impressed that this document was able to recognize this. Like I say, there’s one thing it doesn’t recognize, but otherwise I found nearly all the elements of a critique of the present system, which will lead to the construction of a better system, to be here.

So just to quickly summarize, it enumerated the following things:

frequent crises,

persistent trade and current account imbalances,

elevated and rising levels of public debt,

destabilizing volatility of capital flows and exchange rates.

I mean, that’s a pretty comprehensive list of problems. It also states that it serves the interests of the advanced economies. Capital is flowing from poor countries to rich countries. This is not what’s supposed to happen, but it’s what is required for the functioning of this system.

So, boy, I thought it was a pretty darn good report. Please go ahead and share your thoughts, or, you know, we’re not closing yet, but yeah.

KATHLEEN TYSON: I just want to note that there was a big story that broke that I think is a signal. The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) announced that it was going to split into HSBC West and HSBC East.

Now, it could be that behind that is some horrific debts in the Hong Kong property market. That’s what I’ve heard from one person.

But it could also be that they want to free HSBC East from the fetters and, frankly, stagnation in HSBC West.

The West gets pretty much zero growth. The United States is growing at 2.6%, but that’s only because it’s also running a $2.5 trillion deficit, 8% of GDP. But there’s zero growth in Europe, there’s zero growth in the UK, there’s zero growth in Japan. Although I don’t know where Japan is between East and West. There’s zero growth in South Korea.

So, it looks like what HSBC is trying to do is unite the pro-growth countries of the East in one segment and the pro-sanctions, war-mongering, zero-growth countries of the West in another segment.

If that becomes something that many financial and non-financial firms adopt, either formally or informally, as a structure for governance, that will radically change the balance in the world.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, Kathleen, I’m very glad you mentioned that, because that was on my list of questions. You read my mind there.

So, before we conclude, I would like to go back briefly and talk about this problem -- it’s a very difficult problem to solve, and I think you would be one of the best-equipped people to try to solve it -- which is how to de-dollarize savings, especially the reserves of BRICS countries.

If you read the Russian proposal, you can see that they suggested several different ideas. They even call for the creation of what they call a BRICS digital investment asset, which is based on the assets contributed by the BRICS countries, and it would be overseen by the New Development Bank.

They also, as I mentioned, call for the creation of new investment opportunities through different platforms and the creation of new financial assets denominated in national currencies.

But essentially, as you acknowledge, what we’ve really seen is that central banks have just been buying up huge sums of gold.

The price of gold is rising very quickly, potentially to $3,000 per ounce, and probably well beyond that. Many investors believe it will keep going up.

What’s interesting is that gold is getting a lot of attention, but silver is also increasing significantly, likely because many investors think the gold price might be too high, so instead they’re buying silver, which also has more industrial applications than gold.

However, what has gotten less attention is that China has been importing lots and lots of extra oil—more than to fill its strategic petroleum reserves. China has also been importing many metals that it can stockpile.

So, do you think commodities will become the new kind of reserve assets?

And also, on this idea of starting with the BRICS grain exchange could be used to settle imbalances, if we’re talking about a country like China, which has a trade surplus of more than $800 billion each year, there’s not enough grain in the world to make up for that, or even many other commodities.

So, how do they deal with this problem where you have such big trade surpluses? Even Russia still constantly has a current account surplus.

So they don’t want to buy too many commodities to stockpile them, because then the price would just go very high in all of these markets.

So how do you solve this very difficult issue of de-dollarizing savings and reserves other than just gold?

I mean, maybe you could say gold will go to $20,000, but other than that, what other options are there? And you said you don’t like the SDR option either, so what are the options?

KATHLEEN TYSON: Well, I'm definitely against some synthetic crypto thing. No matter what.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, that’s all three of us. We’re all on the same page there.

KATHLEEN TYSON: All right on stockpiling, China announced two years ago that it’s moving to a war footing, that it sees all the new missile bases that the United States has negotiated in Australia, the Philippines, Japan, and Korea, and it sees the missiles being installed.

So, China is stockpiling everything, and it has the world’s largest stockpile of grains, and now oil. It is entirely rational, because it can be isolated for however long the duration of the war is. So, metals that they might need for manufacturing and stockpiles of oil and grains are protecting them and providing stability.

I mean, one reason why China did not experience a spike in inflation in 2022, when everybody else did, is because of their stockpiles. Their inflation peaked at 3.2%, because they had the world’s largest grain stockpile, and they had an oil stockpile.

Yes, they’ve tripled the strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) in China, so that the United States, under Joe Biden, has emptied the SPR in the United States into China’s SPR, because it basically got exported off to China. Uh, nice, interesting policy. But there it is.

So now the United States doesn’t have a strategic petroleum reserve, because it was used to influence the election. That’s kind of insane, but there it is.

But China’s behavior is completely rational and completely pro-stability, pro keeping inflation low, keeping its people fed, keeping the lights on, and keeping its industries expanding. That’s how it should be seen.

Now, that’s completely separate from looking at those things as some sort of monetary reserve. They’re much more important from the monetary policy perspective of ensuring future low inflation and future availability.

In terms of the rest of the world, Russia doesn’t need to reserve anything, because they make everything. They have every possible resource they could ever need, particularly in light of the size of the Russian population. They want a bigger population; that’s their objective now.

RADHIKA DESAI: That might be the hardest one to crack.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yeah, every country is different in both what it produces and what it needs.

I think actually what would be interesting—and I've never seen it proposed in any Western media—is to study and formulate the methodology that China has used to achieve such outstanding stability and make that a direction of monetary policy.

I mean, instead of monetary policy being all about the money, make it about stability, and about looking at the fundamental nature of what underpins the economy as what’s necessary to underpin the currency.

I actually had this discussion with Professor Charles Goodhart, who was one of the founding members of the Monetary Policy Committee at the Bank of England and then the Global Financial Stability Board.

What if money doesn’t just have one nature? What if money has a different nature in each economy, that is, the economy at issue?

The challenge of monetary policy should be to stabilize the value of money in terms of the real economy within each country of issue.

We tend to talk about monetary policy as if there’s one monetary policy thesis that suits every currency, but I think that’s nonsense. I think you really need to fundamentally rethink what monetary policy is about in terms of stability in light of China’s decades of success and having stable growth without a crisis.

RADHIKA DESAI: But I think that there is a two-word answer to that, Kathleen, that you may not like, but here it is: it's called financial repression. That’s what we used to call it in the past.

That is to say, a regime organized in such a way as to direct capital towards productive investment, to control external movements, and so on.

This kind of regime was derived in the post-Second World War period, which was one of the key reasons we had a period of extremely high growth and a relatively high level of investment, even in Western countries.

That’s what China has; that’s what the West has abandoned since the 1970s. That’s why the West has such abysmal rates of growth.

Also, regarding the point you made about money having a different nature, of course, money has many aspects. It's supposed to function simultaneously as a unit of account, a store of value, a means of exchange, a means of payment, etc. Different policies will prioritize one aspect over the other.

In the United States, during the neoliberal era alone, we've seen tight monetary policy in the 80s and 90s, followed by extremely loose monetary policy since, as a rule not always, about 2000.

So, we’ve had two quite different types of monetary policies, something people rarely comment on.

But anyway, it’s a very different thing. I completely agree with you on that point: that money is different things, and which side every government emphasizes will determine what kind of monetary policy it will pursue.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Yeah, I think it's a big challenge. Usually, central bankers are brought to New York or London, and they’re told this is the only way you can run your central bank. I think what we need to see is more diversity.

I've always been uncomfortable with IOSCO (the International Organization of Securities Commissions) and the Bank for International Settlements making one-size-fits-all rules and then enforcing those by scrutinizing whether they’re implemented in other markets. One set of rules isn’t right for every market.

And I think we can, with BRICS and the way BRICS is expanding, hope—at least at this point—there's more appreciation for diversity, for experimentation, for studying what works, and replicating what works.

This is the way China runs itself internally: policies are set centrally, but 86% of spending is at the municipal and provincial levels, where there's an enormous amount of competition and experimentation to achieve results. All results have standard monitoring for performance, and they study the outperformance. They methodically analyze and report the outperformance methods and then share that nationally.

Here in the UK, we never bother with that. We just allow everything to fail around us without ever studying why it's failing or trying to correct it, which is a bit maddening.

RADHIKA DESAI: But indeed, I must say we should have you back for another show on all the things that are failing in the UK, particularly water. Maybe sometime, you know, this is such a scandal.

KATHLEEN TYSON: I'm 20 feet from the Thames River here outside that window. So water quality is something I'm passionate about, because when I bought this house, I could swim in the Thames.

RADHIKA DESAI: And you can't anymore?

KATHLEEN TYSON: No.

RADHIKA DESAI: Oh wow, because, well, I have not swum in the Thames, but my dog has many times.

BEN NORTON: Well, it's full of sewage now, right?

KATHLEEN TYSON: It’s an open sewer.

RADHIKA DESAI: I thought they didn't permit it in the Thames, although they permitted it in some of the smaller rivers. But I'm interested to hear they also permitted it in the Thames.

But exactly, and this is a country that prides itself on rewarding the winners. Well, this just doesn’t work that way. You have to take care of everybody.

But anyway, that's for another story.

Maybe I'll just make one final remark in closing and then invite you both to comment, and then perhaps Kathleen and Ben, we will have set up another show discussing these scandals we were just discussing.

To me, as I say, I feel that some kind of capital controls, no matter how you talk about them, are indeed necessary to create the kind of stable, productive state—a financial system that we're talking about.

This report to me comes close to, I mean, it sort of seems like it's on an even keel. On the one hand, it talks explicitly about directing capital flows away from flowing to first-world countries, where they complain it is flowing unnecessarily and to the detriment of emerging markets, and towards emerging markets and productive investment. But on the other hand, they don’t really discuss capital controls in any way.

To me, it seems that they are poised on a knife edge between the need to recognize this but, on the other hand, the pressures upon them not to name such a thing as capital control.

So how this unfolds in the future will be most interesting. That’s what I wanted to say in closing, but please go ahead, Ben and Kathleen, whatever you want to add.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, Kathleen, I know I've mentioned this, and I agreed with the answer that you gave; I agreed with everything you said about how each country's economy is different; we shouldn't take this one-size-fits-all approach that is often taught in finance classes and such; and central bankers are taught they should all run their central bank the same way.

But really quickly, to get back to this question: you mentioned that China has been buying up a lot of different commodities and trying to convert—essentially find new forms of converting its current account surplus, its big trade surplus, into something that it can tangibly use for the economy.

I would add that also it’s been using a lot of that surplus to fund the Belt and Road Initiative, right, to turn that surplus into tangible infrastructure.

But the point is, if you were in the People's Bank of China right now and you saw what happened to the Bank of Russia -- $300 billion U.S. dollars and euros worth of assets stolen by the West -- and you said, "OK, we need to find some kind of alternative”.

Obviously, the PBOC is selling Treasuries and buying a lot of gold, but unless we really do think that gold is going to go from a bit under $3,000 like it is now to, I don't know, $20,000—who knows how much—it’s very possible the price could just multiply many times.

But do you think that there are other assets that could be held? Like, is there a short-term solution? Or does there need to be some kind of medium to long-term solution?

And could that not be something like something like a Bancor, something that can’t be seized by the U.S. and Europe?

KATHLEEN TYSON: It's a bit complicated and uncertain, because it wasn't as obvious in this BRICS summit.

Last year in Johannesburg, I was pretty much keeping a tally of all the bilateral deals that were announced. You know, the Dubai Ports World was going to build the first super container port in India. India has an amazing long coastline, but not a single super container port for export. So, DP World is building that.

And then Saudi Arabia agreed to sell oil for a nuclear power plant that China would build in Saudi Arabia.

And, you know, China's electricity company was going to fix the grid in South Africa, which, by the way, they did. South Africa hasn't had a brownout or blackout for six months as of today's date. So, Eskom was a complete mess, so it seems like that cooperation benefited South Africa almost immediately.

Though I have not seen those kinds of bilateral deals being announced this week, that doesn't necessarily mean they're not happening. And that is a critical use of surpluses.

Dubai recycled its surplus into a new container port in India that it co-owns. China recycles its surplus into nuclear power plants that it's building all over the world now and, as you say, into logistics infrastructure, railways, ports, hospitals, universities, and things that can grow domestic economies that then become future clients of China's exports. If it grows African prosperity, that's a huge game-changer in terms of new markets for Africa for Chinese goods.

In terms of Treasuries and why, you know, why would China not be dumping Treasuries? They're not dumping Treasuries. A year ago, they had $805.4 billion in U.S. Treasuries. These are their official and non-official holdings together. And right now, it's $774.6 billion, so they're down $25 billion. That's not dumping. They're not dumping their Treasuries.

You know, obviously, right now, the United States military is hugely concentrating in the eastern Mediterranean for a war with Iran. And there have been huge upspikes this month in inbound cargo flights and in F-35s, F-16s, and refueling tankers concentrating in the region. So, we're going to have to see how that plays out.

But as long as the United States is tied down in the eastern Mediterranean, then it's not going to have a war with China.

And so, China will encourage the United States to not attack China by holding on to those Treasuries, and it's a relatively low cost at $770 billion. You know, that's just a drop in the bucket to them.

U.S. trade with China is now less than 10% of China's trade. So, if there was a war, China could cut the U.S. off, and China would hardly feel it, but the U.S. economy would implode.

And we're seeing the Israeli economy implode right now because you just can't do business with Israeli companies anymore. A lot of people are quietly backing away and de-risking from exposure.

So, there's a lot at play at the moment. It's a very confusing world. But what I think is possible as an alternative to large surpluses is co-investment, and that does get a mention in the Russian report.

I think they called it blended finance or something, which, by the way, is also Sharia compliant. So, it’s important for the Muslim countries in BRICS because co-investment is completely okay.

And again, it's long-term stabilizing, because if you're partners in an enterprise instead of just ripping it off like asset stripping or whatever, then you're building future prosperity and future stability.

So, I think the world is changing very quickly. Parts of it are very dangerous, but there's a lot to be hopeful about, particularly in the East, and the Far East, and in the Global South.

We have seen the Sahel states declare their independence from French imperialism, kick out the military bases on their soil, and nationalize resources. Now, they're importing tractors and fertilizer. Burkina Faso has imported 1,000 tractors. That's a game-changer, because food security is national security.

So, I started out with currency optionality as national security. Food security counts too, so there are a lot of changes going on, and many of them are very positive towards long-term stability and long-term shared prosperity.

I want to end there on a positive note and hope that the rest just sorts itself out.

RADHIKA DESAI: I think that's a great note to end on. At the end of the day, what are you going to buy with the money if it's not food in the first place? So, absolutely, food security is important.

I just wanted to add two quick things. Well, you know, this whole issue of investment being used as a way of dealing with the problem of overaccumulation of currencies was also, of course, in Keynes's original plan for the Bancor. He said that this would be a form of development loans and so on that could go to other countries if there was accumulation of reserves beyond a certain point.

But above all, his plan was a plan for development, which he felt would lead to balanced trade, because the more balanced trade and investment relations are, the less need there is to settle any outstanding imbalances.

The other very quick point is that, you know, this whole issue of China dumping dollars, or not dumping dollars as the case may be in this discussion, most people forget that the overwhelming majority of U.S. debt is owned by U.S. individuals and entities; it is not owned outside the U.S.; that accounts for almost 70% of the total. Then the rest is divided among various foreign holders, of which Japan is currently the largest, but China was once the largest.

But, Kathleen, thank you so very much. I think that your expertise is so much appreciated on this show. We really enjoyed it and hope to have you back to discuss a million other things, which I'm sure you can shed lots of light on. So, thank you very much.

Thanks for joining me, Ben.

We look forward to the next Geopolitical Economy Hour in about 15 days. Please like it, share it, and discuss it, of course. Thanks very much, and goodbye.

KATHLEEN TYSON: Thank you.

Rhadika pointed to the most crucial issue, and I dont know if it was really given the attention it deserves:

"While the BRICS must aim at productive, dynamic, innovative, exclusive, and egalitarian economies, that is not the direction in which Western economies are going."

This is not a trivial matter. The western countries have parasitic economic values: they prey on their own masses.....and on foreign economies that they turn into vassals, sucking out their resoruces and wealth. They dont do this by diplomacy, as there isnt any win-win in it, so countries cannot be conviced by any positive reasons.

They way they do this is

a) by coopting corrupt leaders, such as were recently deposed in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso

b) by coups and invasion

So the BRICs and the global south need to to be clear that de-dollarization effort (to be more specific its basically an economic detox to remove dependency on the US and its vasals ) will come with even MORE violence from the west than we have seen so far. What they have done in Ukraine, they will keep trying to do elsewhere. Again and again. Massive violence.

This is not only in the form of national armies. Look at Pakistan where there is "terrorism" in places where China is building infrrastructure. Look at West Africa and the Sahel where "ISIS" and "Boko Haram" seem to pop to to attack those two are not completley subjugated or to keep them in line as a threat. The same happened in Syria and LIbya too.

So beyond the tehcnical-financial issue, the BRICS and anyone looking to do this has to expect violence incoming.

Kathleen nailed it. As good a summary as you'll find anywhere.