1917 and Hollywood’s false dichotomy between humanizing and politicizing war

Sam Mendes’ 1917 is the latest in a series of contemporary Hollywood films that are works of jaw-dropping technical brilliance that ultimately serve to glorify World War I by depoliticizing it.

As with Peter Jackson’s breathtakingly beautiful — and equally apolitical — WWI documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, which I wrote about in December 2018, I must preface this present review by pointing out the obvious: On a technical level, 1917 is a masterpiece.

The entire two-hour movie is comprised of just a small handful of extremely long tracking shots — an artistic feat of unimaginable difficulty. Considering how obscenely hard it would be to shoot all of this action and make it look like one continuous shot, while keeping the audience immersed in the drama, 1917 cinematographer Roger Deakins and the whole camera crew deserve many a pat on the back. And given these enormously demanding technical hurdles, the acting is top-notch too.

But as a social and cultural work of art, 1917 is very mediocre. The film has little to say, and honestly tries to say little. It is a pretty-looking work of artifice. It goes to great efforts to depoliticize, while also humanizing, the most senseless, stupid imperialist mass slaughter in modern history, World War I.

1917 is a perfect example of how Hollywood values aesthetics above all else. It looks amazing, but there is not much beneath the surface.

Because at the end of the day,1917 is really not about World War I. WWI is just the backdrop. 1917 is a story about overcoming your personal obstacles and never giving up. The film is utterly disinterested in politics.

There is some complexity to the characters; it’s not all just rah-rah warmongering. Before the protagonist and his friend leave on their impossibly dangerous journey, the young grunts (canon fodder in the British empire’s war machine) are cautioned to make sure that there are witnesses when they deliver the message to their commanding officer, because some generals just want more war.

A superficial reading might see this scene and conclude that the film is anti-war, or at least pro-peace (the two are not necessarily the same). After all, the protagonist’s guiding mission is to deliver a missive that could prevent an impending battle that would lead to hundreds or thousands of pointless deaths.

But never once considered in the movie, not even for a moment, is that the entire war itself was equally pointless — and that all deaths, therefore, were pointless, even if they were not lost in a strategically foolish move or a German trap.

Like most liberal Hollywood movies, 1917 has some depth to it; it’s not Michael Bay-style bellicose nationalist propaganda. But the film is simultaneously deeply depoliticized — even though it’s about war, which is the most political act of all!

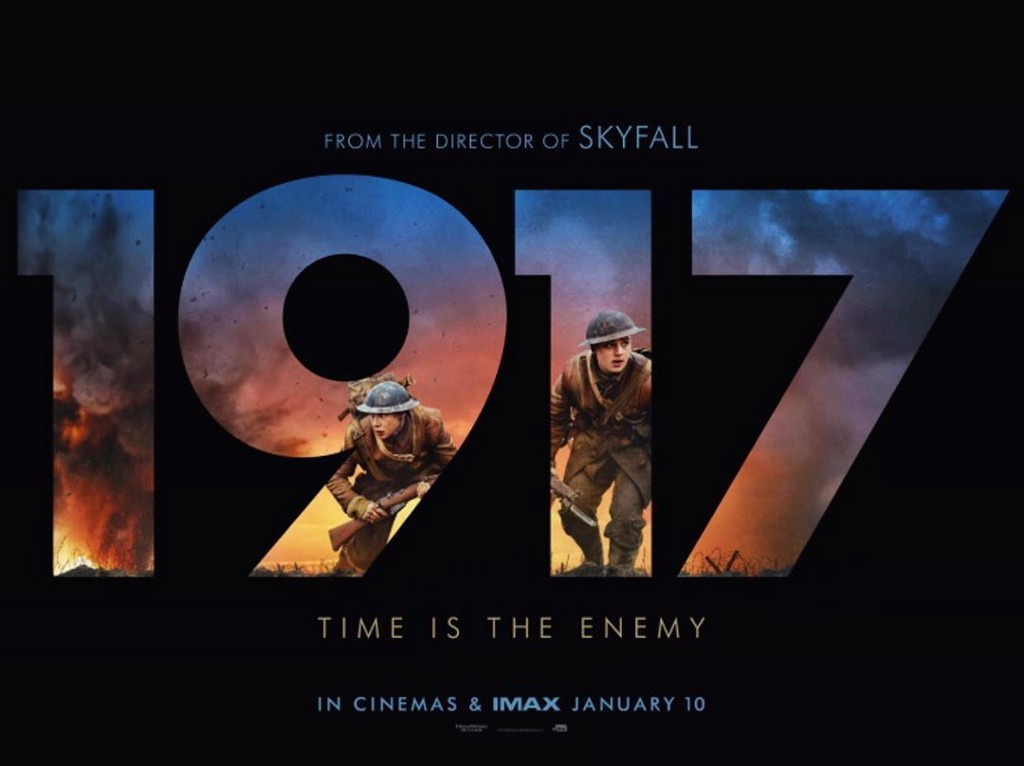

In fact, the tagline on the 1917 poster is “Time is the enemy.” Not war, not imperialism, not even the Germans, but rather time.

War is not the problem, in the universe of 1917; rather the issue is with the technocrats overseeing war, who may sometimes drink a little too much of their own koolaid.

I am not arguing that 1917 is an actively pro-war movie. If a right-wing jingoist had directed it, it very well might have been. When I say it depoliticizes the war, that depoliticization goes both ways.

But by being apolitical, the film passively justifies war.

The internalized ideology of 1917 is reminiscent of those liberals who say the Iraq War was bad not because it was a criminal invasion and occupation built on imperial aggression and lies, but rather because the war-hungry neoconservative barbarians overseeing it were overzealous and unstrategic.

At the same time, the film also has a subtle, cynical jab against anti-war critics. When the lead characters do show solidarity with fellow humans across borders, they are punished. When the British grunt tries to rescue the German pilot, he pays the ultimate price, tragically bleeding out on a hill in the middle of nowhere. The lesson we take from the episode is that anti-war skeptics might sound nice, but pacifism will get us all killed — war is war, the other side is the enemy, and there is no room for empathy.

1917 also demonstrates how Hollywood loves to draw a false binary between politicization and humanization. In a movie about mass industrial-level imperial slaughter, it strives to center the film not around the war, but rather around a single human at the center of that armed conflict. Most of the time, Hollywood movies do this at the great cost of removing political and historical context. (There are a few honorable, and rare, exceptions, take Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket or Oliver Stone’s Platoon.)

But this is a false dichotomy. The best films can humanize war without depoliticizing it, showing the horrors in a way that ultimately serves to delegitimize war itself — and simultaneously without turning the characters into cheap emotionless props in a propaganda exercise.

It would also be remiss to not include a word about the title… For a socialist, it is nothing short of sacrilege. 1917 is the year the Bolshevik revolutionaries effectively ended the inter-imperialist mayhem of World War I, withdrawing from the senseless bloodbath that saw millions of working-class people poured into a slaughterhouse for no reason other than protecting their respective capitalist state’s colonial possessions from another capitalist state. But for Hollywood liberals, 1917 is the year some Brits did a brave thing.

1917 ultimately reflects the liberal ideology that is hegemonic in Hollywood. It it not a morality play that glorifies World War I as something good, as a proudly reactionary director like, say, Clint Eastwood might do; but it also does little to nothing to challenge the idea that World War I was necessary.

Embedded within the film, even and especially with its subdued critiques of the war-makers (not the wars, but the war-makers), is the prototypically liberal notion that wars are bad, but tragically necessary.

Originally published at https://bennorton.com on February 10, 2020.